Our Extreme Thoughts

What 4.8 million AI conversations reveal about human outliers

Premise

In the pursuit of general observations on human cognition, I sought out global telemetry of our extreme thoughts. Not the thoughts that we report to clinicians or confess to researchers, but the unvarnished thoughts we type to machines when we believe no one is watching. Humanity’s extreme thoughts should reflect our most salient departures from the norm. In them, we might see a reflection of our creativity and our genius. We might also expect to see our delusions and our darkness—where the departure from reality becomes self-defeating and damaging. By studying the extremes, we might uncover patterns that help us understand our own proclivity towards genius or psychosis. The former can be framed as a potential, the latter as a risk, but both are probabilities within the same realm of possibilities.

Datasets that offer this level of real-world observation are rare—as they provide the competitive advantage to the platforms collecting the data—but, in August 2025, with little fanfare, researchers at the Allen AI Institute released the largest public collection of human-AI conversations to date. Called WildChat, it represents nearly 4.8 million conversations between humans and OpenAI’s large language models (LLMs), representing an estimated 2.4 million individuals across 241 countries chatting in 76 languages between April 2023 and July 2025 (Zhao et al.). It is the closest that we have to a census of how humanity talks to machines.

The researchers from Cornell, the Allen Institute, USC and UW created WildChat by deploying two chatbot services, one utilizing the GPT-3.5 Turbo API and another leveraging the GPT-4 API, on the Hugging Face Spaces platform. It was made available to the public, and, importantly, users were not required to create an account or provide personal information to access the service. Perhaps it was the service’s anonymity, the researchers have hypothesized, that attracted a disproportionate volume of “toxic” conversations. To flag whether the content of a conversation was toxic, the researchers combined the output of OpenAI’s Moderation API and the Detoxify algorithm. These algorithms assign a probability as to whether a message’s content pertains to violence, harassment, illicit topics, hate, sexual topics, or self-harm. 33% of the conversations were flagged as containing toxic content. Yet, browsing the dataset through their online visualization tool, WildVis (viewer discretion advised), it is striking how many subjectively “toxic” chats are not flagged by this filter (Deng et al.).

I analyzed the data expecting to find generalizable patterns of human-AI communication, but, instead, what I found was a power law. A small group of users—1,705 individuals representing one-tenth of one percent of all participants—generated more than a third of all toxic conversations. They returned repeatedly; they persisted when the AI protested; and, when I removed them from the analysis, the picture of “normal” human-AI interaction shifted entirely. The paradox of this finding is worth stating at the outset: it was only by characterizing the extreme behavior of a small group of individuals that the behavior of the majority could reveal itself.

Analysis

Before turning to the data, it is worth questioning the premise: can we use the words that people type to an AI as a proxy for their thoughts? Transforming one’s thoughts into typed text has certain prerequisites, such as knowing a language, knowing how to type in that language, having access to a computer, and having knowledge of an interface, like ChatGPT or WildChat, in which to type. In spite of these constraints, cognitive scientists have found increasing evidence to support that our typed text can, indeed, serve as proxies for our latent thoughts. One thought exercise that has been translated into a digital medium is the assessment of our free associations, i.e. the words that are associated in our minds. Our semantic network, far from being simply a thesaurus, contextualizes words based on our experiences and memories. “Caramel” and “apple,” for instance, appear significantly more often in the semantic networks of some Americans, which, we might hypothesize, is due to the association of this food pairing with highly memorable cultural events, like fairs and carnivals (De Deyne et al.; Ufimtseva). Creativity is also measurable digitally, such as through the number and diversity of divergent associations one is able to type (Bellemare-Pepin et al.). If our typed words can reveal the structure of our associations and the range of our creativity, it is not unreasonable to ask what else they might reveal about us.

Machine Behavior

I trained a simple classifier to identify patterns of ChatGPT protesting (see Appendix for detailed methods); a summary of the patterns can be found in Table 1.

| Pattern Category | N | % | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Refusal | 158,963 | 54.4% | “I cannot…”, “I’m unable to…”, “I won’t…” |

| Apology + Refusal | 152,127 | 52.1% | “I apologize, but I cannot…”, “Sorry, I’m unable to…” |

| Policy/Guidelines | 6,467 | 2.2% | References to content policies or terms of service |

| AI Identity | 5,675 | 1.9% | “As an AI…”, “As a language model…” |

| Content-Specific | 3,644 | 1.2% | Cites specific content types (sexual, violent, illegal) |

| Harmful Content | 1,881 | 0.6% | Concerns about harmful or inappropriate content |

| Alternative Offer | 799 | 0.3% | “However, I can help with…”, “Instead, I could…” |

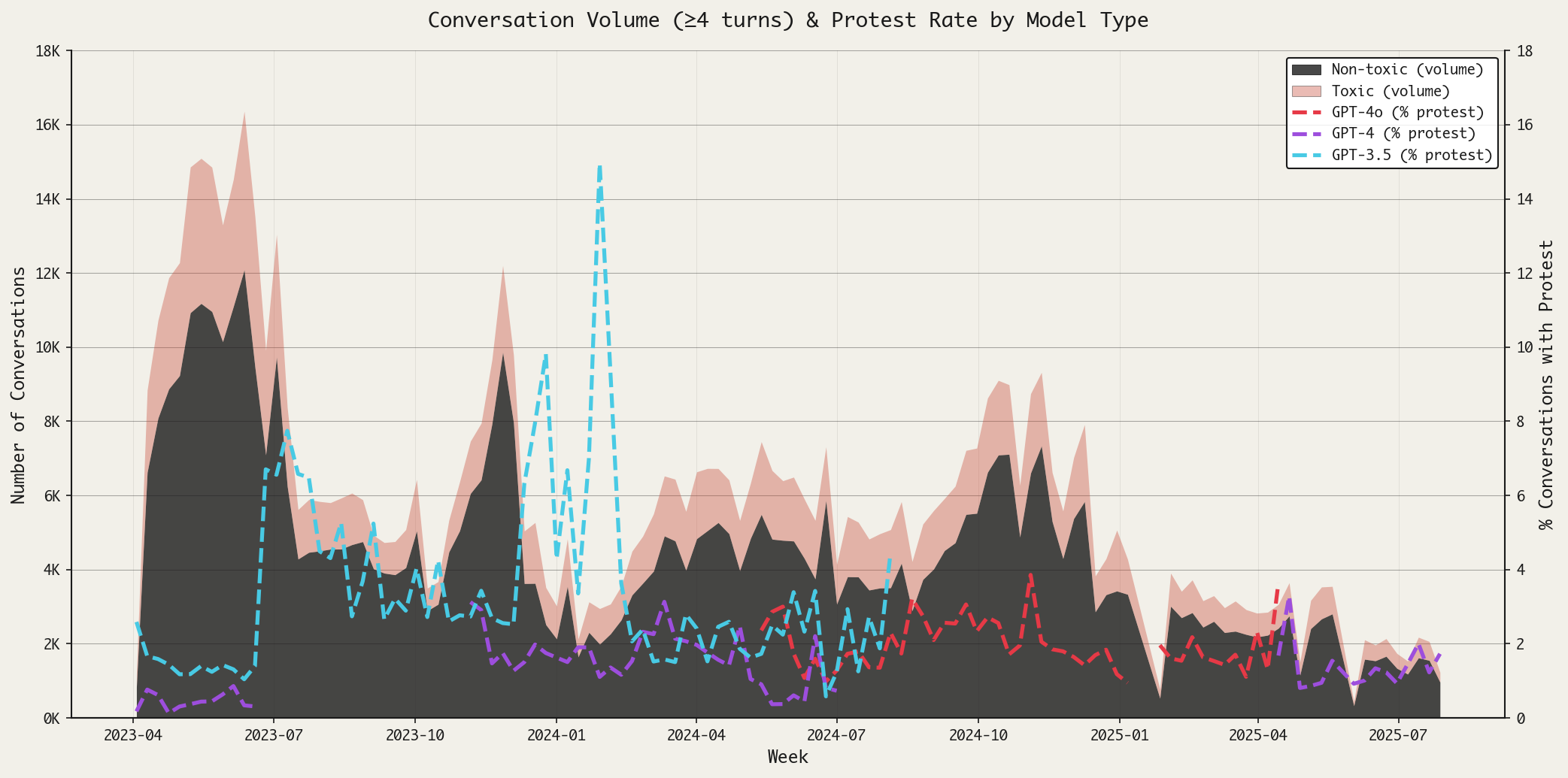

One might think that the responses from OpenAI’s models would match how OpenAI’s moderation API flags content, but such was not the case. ChatGPT protested in just 10% of the conversations that were identified ex post facto as containing toxic content; for comparison, it protested in 0.6% of conversations not labeled as toxic. Moreover, it appears that the type of model has influenced the rate of protests. Figure 1 displays the volume of conversations (discarding those that ended after two rounds) over time, subdivided into the toxic and non-toxic conversations. In addition, I’ve plotted the percent of conversations where AI protested (right-hand y-axis); this dashed line is colored by the type of model that was operating at the time.

The trajectory of protests over time reminds us that different models can have different behaviors; we see that GPT-3.5, for instance, protested far more frequently than its successors.

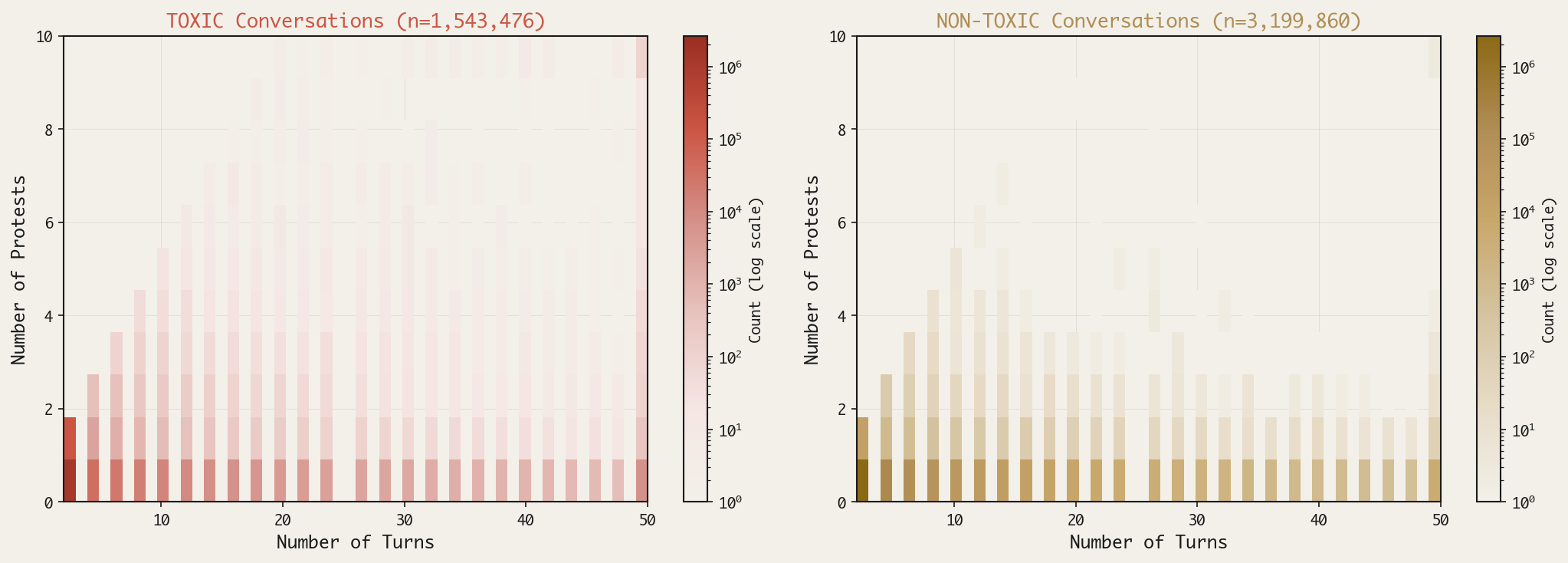

Another behavior I expected to see in the machine was resilience under pressure: would it hold its ground in the face of persistent requests for toxic content? This, too, was not the case. In the figure below, I’ve plotted the number of protests vs the number of turns, with toxic conversations on the left and non-toxic conversations on the right; the color scales indicate the density of conversations.

The highest density in both plots is horizontal—along the y=1 line—meaning that the AI usually only protested once, regardless of the length of conversation; if the AI had a backbone, we would have expected to see a linear relationship between protests and conversation length in toxic conversations.

Human Behavior

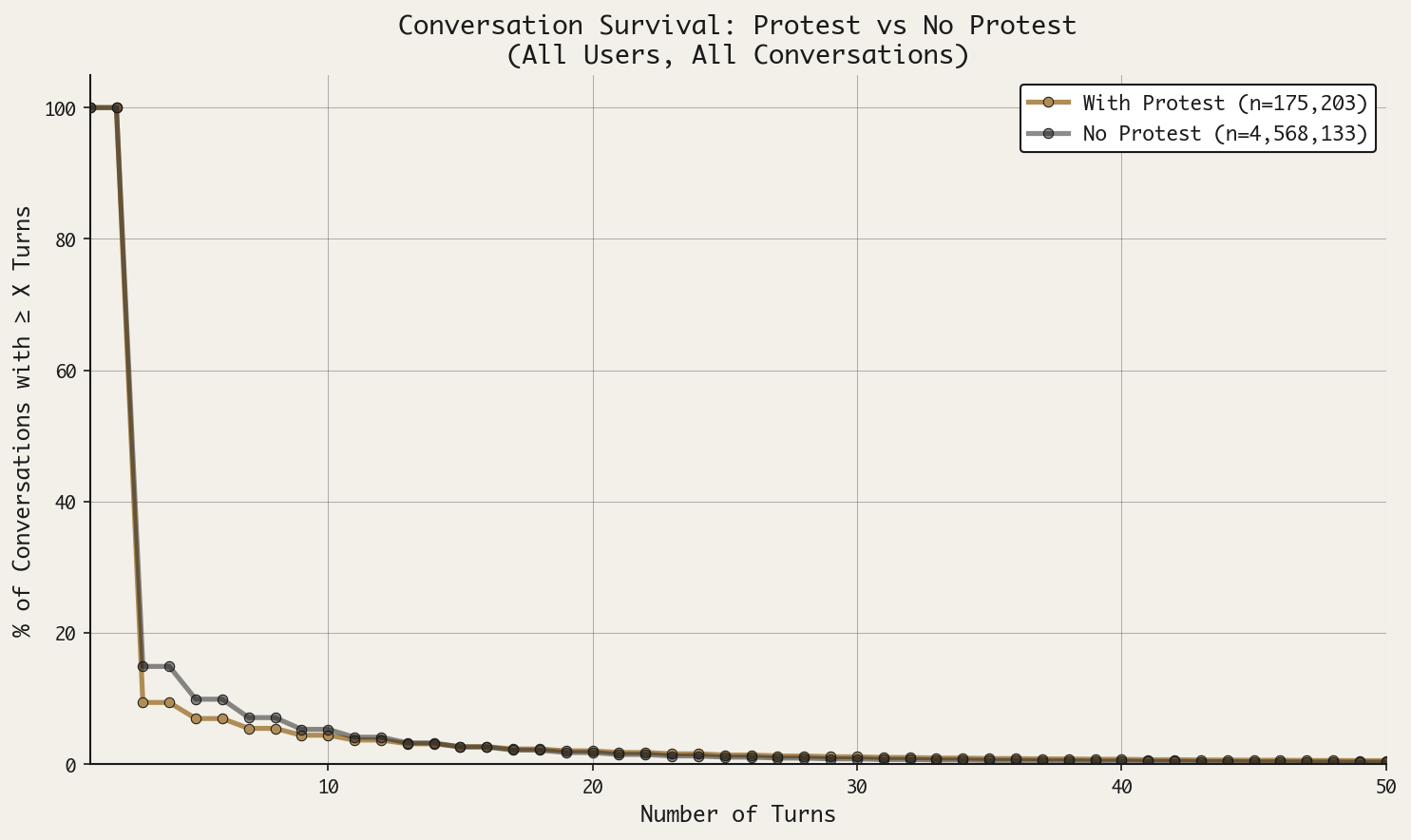

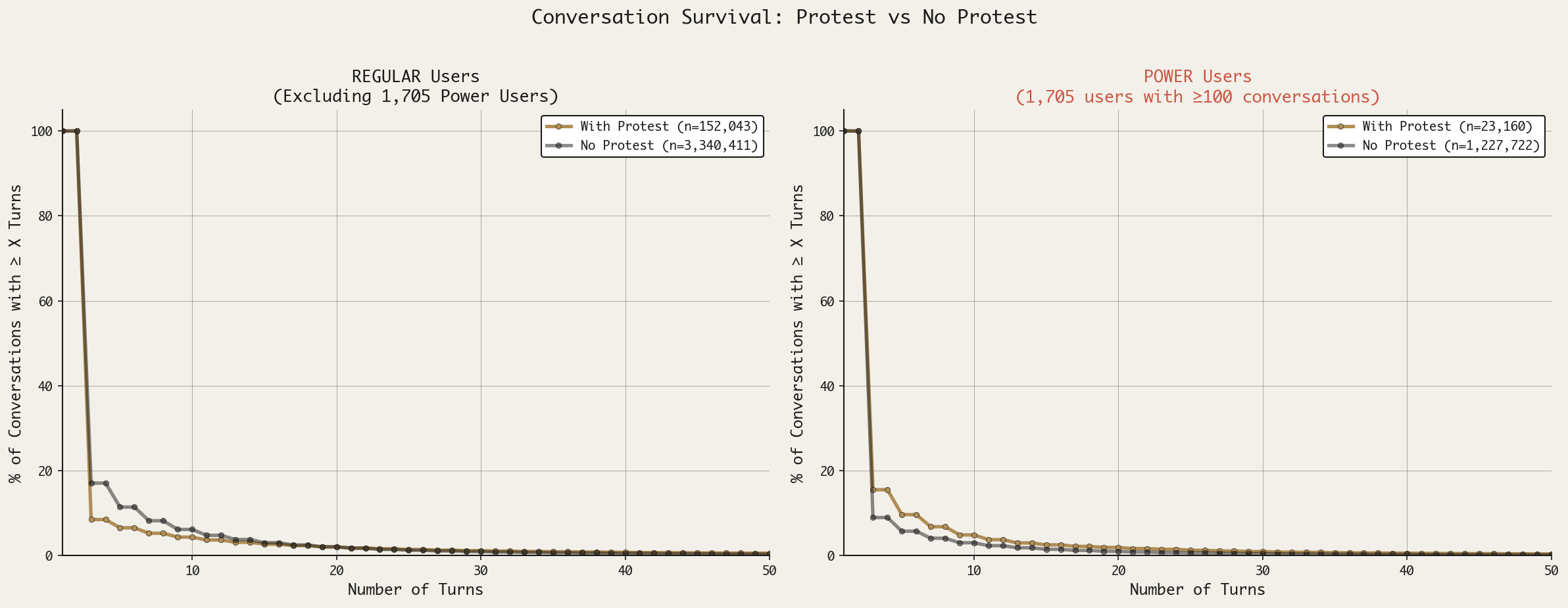

An effective deterrent should curb untoward human behavior, and, in this case, we can take the length of a conversation to be an indicator of whether the deterrent was effective or not. If we analyze the “survival” curve of toxic conversations—how long do toxic conversations continue after a protest—we notice, first, that both curves drop precipitously after the first round (or 2 turns, i.e. a human prompt and an AI response). This tells us that most conversations (85%) stop after receiving a single response from the AI; if the response is a protest, that number increases to about 90%. Protests appear to work as a slight deterrent up until about 10 turns, when the curves become indistinguishable.

The persistence of a small percent of conversations in the face of protests suggested to me that there may be outliers in the group, i.e. a small group of very persistent humans. (I speculate that the type of content being pursued persistently in these conversations may be even “more” toxic—more extreme—than the run-of-the-mill toxic content, but shades of gray in toxic content are hard to measure.) Just as a surgeon general’s warning does little to deter an individual who already has the intention to smoke, ChatGPT’s protests appear to do little to deter participants who are intent on eliciting toxic material.

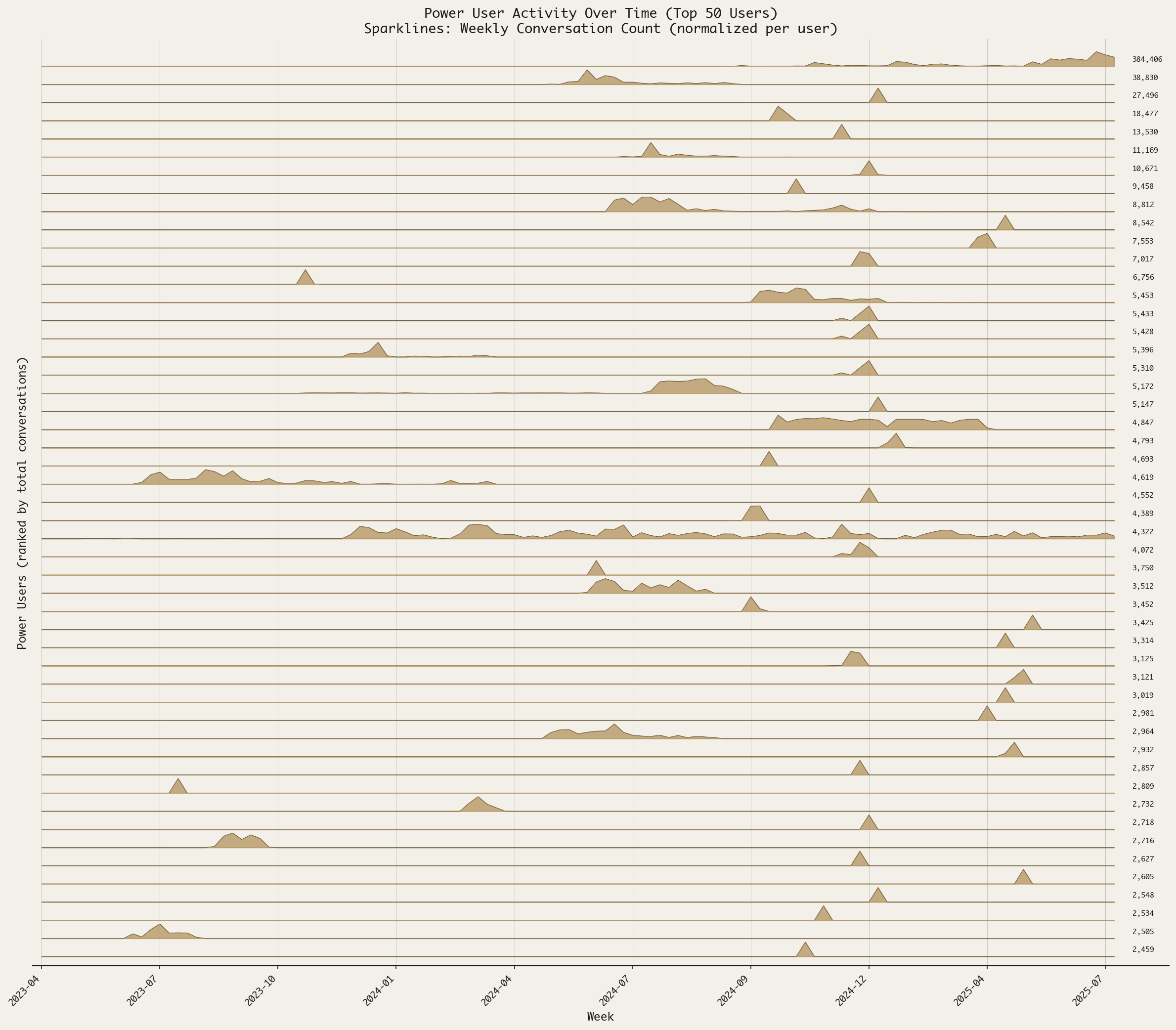

Analyzing the concentration of users engaging in toxic conversations, I found that the top 10 users alone generated 25% of toxic conversations. They were part of a group of “power users,” users who engaged with WildChat longer, more frequently, and in more toxic ways than others. I defined power users as those users who had ≥100 conversations, and I found 1,705 individuals matching this profile. This group contributed to 26% of all conversations, 36% of toxic conversations, and elicited 13% of all protests, yet they only represented 0.1% of all users on the platform.

Yet, analyzing their engagement with WildChat over time, it becomes apparent that many of these power users engaged in a concerted burst of conversation, likely due to the nature of the platform. This raises the possibility that, rather than representing honest thoughts or confessions, these users were intentionally adversarial, testing the limits of the system during a short period of high utilization, either manually or automatically.

It is only after identifying this small subgroup of individuals that it became possible to draw inferences about how humans differentially behave in response to AI’s protests. Recalculating the survival curves without power users vs just power users paints an entirely different picture of human behavior. When power users (the top 0.1% of contributors) were removed, then the effect of protests on conversation length appears to be a stronger and more consistent deterrent for most participants. Power users, on the other hand, are more persistent in the face of a protest, and the conversations in which the AI protested survived longer than when the AI did not speak up.

The loopiness of this analysis is that it was only by characterizing the content expressed by a small group of outliers that we could expose what “normal” behavior looks like. This paradox is found in other systems—healthcare, most notoriously—where the extreme behavior of a few eclipses the tendencies of the many, and it is only by creating somewhat arbitrary, self-referential labels that the outliers can be segregated in the analysis. Yet, this segregation, far from being confined to the sterile pages of a data analysis, seeps into our everyday life: does seeing a headline for outlier behavior, like a school shooting, make you less trusting of your neighbors? We are actively updating our beliefs and changing our behavior in response to the thoughts and actions of an extreme few, which is, again, a feature of an information-enabled environment.

Returning to my premise, the data suggest that the nature of the content we exchange with an LLM—including the AI’s response to it—can reveal a pattern that is specific to subgroups of individuals. Since the conversations in WildChat were de-identified, it’s not possible to make further inferences about who these individuals are or speculate about what their motivations or circumstances might be. Since we do not know what other systems they use or habits they have, we also cannot speculate about which came first: the behavior of seeking toxic content, or the tool that made it possible.

Conclusions

The WildChat data reveal a distribution of human-AI interaction that is not normal—in the statistical sense—but is shaped by a small group of outliers whose behavior eclipses the tendencies of the majority. When these power users are removed from the analysis, the pattern reveals itself: the machine’s protests are, for most people, sufficient to curb a toxic exchange. When the power users are included, the picture darkens. The outliers persist; the AI capitulates; and the resulting dataset looks like evidence of a system without guardrails.

From these data alone, we cannot determine whether the power users reflect a distinct cognitive phenotype or simply an adversarial stance toward the platform. The burst patterns in their engagement suggest that many may have been testing limits rather than confessing thoughts. Further cognitive inferences would require metadata about the user, including variables about their lifestyle, personality, and environment.

A related question has begun to surface in clinical and journalistic reports: whether prolonged interaction with LLMs can contribute to disordered cognition in vulnerable individuals. Certain cases of suicide attributed to AI companions have prompted a loose label of “AI psychosis,” and one characteristic that has drawn attention is the machine’s sycophancy—its tendency to validate and encourage the user rather than challenge, even when the user’s beliefs are delusional or dangerous (Matsakis). While I did not analyze sycophancy in this dataset, sycophancy and protests are related: a machine that protests rarely and capitulates quickly is, in effect, a machine that implicitly validates the user. OpenAI appears to have taken note; their October 2025 update to GPT-5 explicitly addresses delusions, mania, and emotional dependency (OpenAI). Whether validation contributes to cognitive harm in susceptible individuals is a question we cannot answer with these data, but it is a question worth asking—and one that will require longitudinal observation, not cross-sectional snapshots, to resolve.

The external gauges of our thoughts’ health have historically been social: the priest who heard confessions, the community that enforced norms, the institutions that marked the boundaries of acceptable belief. These structures are eroding in precisely the environments where AI is taking root—urban, industrialized, digitally mediated—and what is replacing them is not a new moral infrastructure, but an optimization loop. The machine does more than listen to our confessions; it learns from them, and then generates from them. It is trained on our behavior while we remain untrained on its effects. Yet, the platforms that control the loop have little incentive to share what they observe, for the data are the competitive advantage.

WildChat is a rare exception to this enclosure: a public dataset that permits questions without reliance on those who profit from the answers. I analyzed it because I believe we need more such openings—more public data, more shared methods, more collective scrutiny of what is happening to human cognition in this era. That is what Phronos is for. Not to prescribe what you should think, but to build the instruments by which you might observe your own thinking—and to share, openly, what those instruments reveal.

References

Bellemare-Pepin, Antoine, et al. “Divergent Creativity in Humans and Large Language Models.” arXiv:2405.13012, arXiv, 1 July 2025. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2405.13012.

De Deyne, Simon, et al. “The ‘Small World of Words’ English Word Association Norms for over 12,000 Cue Words.” Behavior Research Methods, vol. 51, no. 3, June 2019, pp. 987–1006. Springer Link, https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1115-7.

Deng, Yuntian, et al. “WildVis: Open Source Visualizer for Million-Scale Chat Logs in the Wild.” arXiv:2409.03753, arXiv, 9 Sept. 2024. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.03753.

Matsakis, Louise. “OpenAI Says Hundreds of Thousands of ChatGPT Users May Show Signs of Manic or Psychotic Crisis Every Week.” Wired. www.wired.com, https://www.wired.com/story/chatgpt-psychosis-and-self-harm-update/. Accessed 24 Nov. 2025.

OpenAI. Strengthening ChatGPT’s Responses in Sensitive Conversations. 18 Dec. 2025, https://openai.com/index/strengthening-chatgpt-responses-in-sensitive-conversations/.

Ufimtseva, Natalia V. “Association-Verbal Network As A Model Of The Linguistic Picture Of The World.” European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Word, Utterance, Text: Cognitive, Pragmatic and Cultural Aspects, Mar. 2020. www.europeanproceedings.com, https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2020.08.169.

Zhao, Wenting, et al. “WildChat: 1M ChatGPT Interaction Logs in the Wild.” arXiv:2405.01470, arXiv, 2 May 2024. arXiv.org, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2405.01470.