What Predicts Who Stays?

The paradox of engagement in human-AI interaction

I. Premise

I began this inquiry with what seemed like a reasonable hypothesis: that the users who form the deepest relationships with AI systems would betray themselves in their language. The psychology literature suggested as much. Self-referential language—the pronouns “I,” “me,” and “my”—has long been associated with deeper cognitive processing and memory encoding. The IT-identity literature documented how people form meaningful relationships with their technological tools, treating them not as mere instruments but as extensions of self. If any population should display elevated markers of self-engagement, surely it would be the power users of large language models—the ones who returned hundreds of times, building what amounted to a sustained relationship with a machine.

The WildChat dataset offered an unprecedented opportunity to test this intuition. Here was a corpus of 4.7 million conversations from 2.4 million users, spanning April 2023 to July 2025—a natural laboratory of human-AI interaction captured without the distortions of survey methodology or laboratory constraints. Users typed what they actually wanted to type, believing no one was watching. If identity markers predicted engagement anywhere, they should predict it here.

What I found instead was a series of paradoxes that forced me to reconsider what “engagement” with AI actually means.

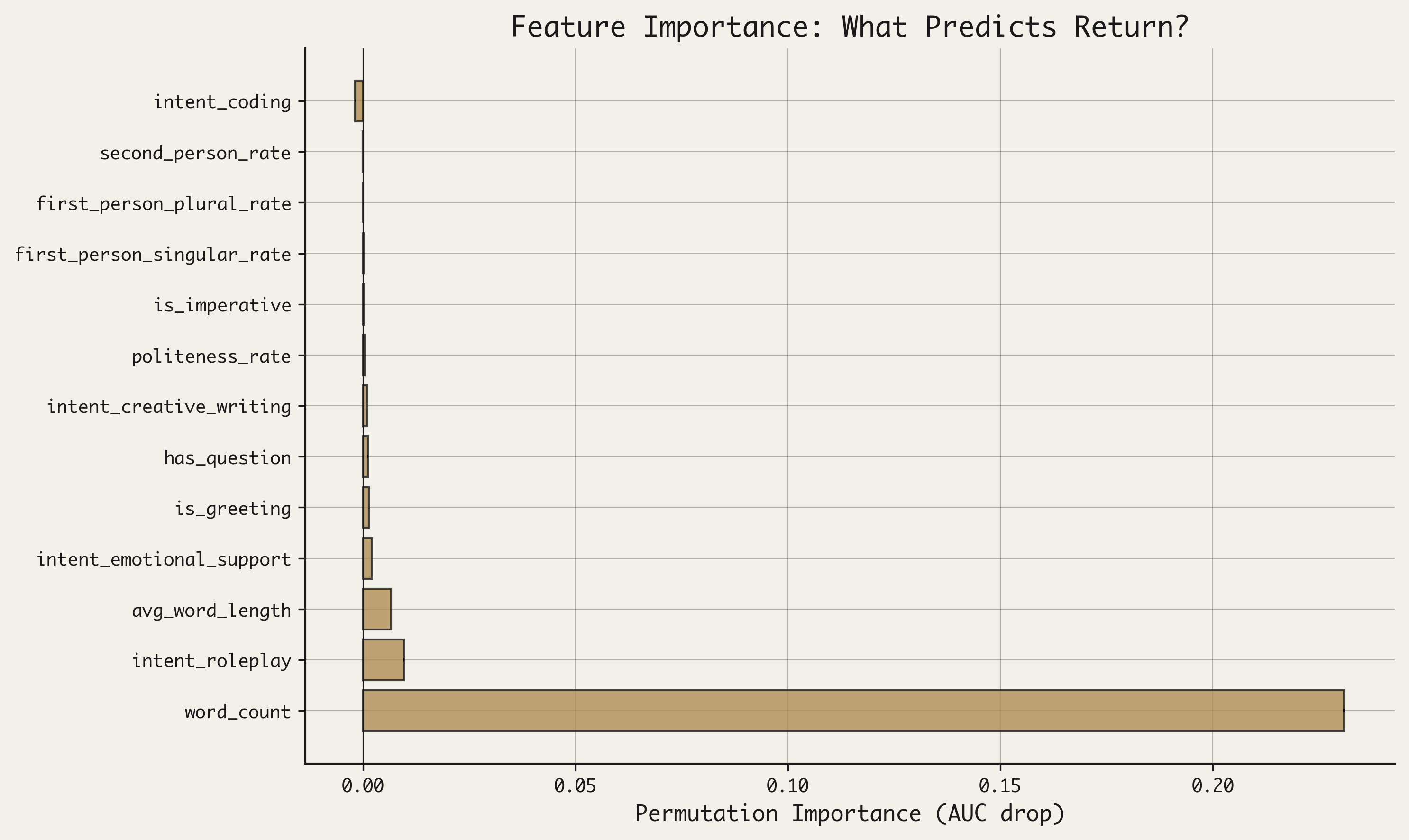

The first paradox: when I trained a classifier to predict which users would return for subsequent conversations, word count alone—a simple proxy for task complexity—achieved nearly the full predictive power of the model. The elaborate machinery of identity detection contributed almost nothing. Users who typed more came back more. What they said about themselves barely mattered.

The second paradox: when I examined power users descriptively, I found not elevated self-reference but its inversion. The users with the most conversations showed lower rates of first-person pronouns, lower rates of direct address, and lower rates of politeness markers than moderate users. The expected pattern was not merely absent; it was reversed.

The third paradox: when I applied the logic of “concerning use detection”—flagging sessions that were extended, intensive, and sustained—I found that most sessions meeting these criteria were benign. The plurality were simply curious users exploring diverse topics. Duration, it turned out, was a poor proxy for distress.

These paradoxes share a common thread, one that became clearer as the analysis progressed. Before I could understand what predicts who stays, I had to understand what fails to predict it.

II. The Identity Hypothesis

II.A The Intuition

We remember what we connect to ourselves, i.e. the self-reference effect. When people judge whether a word describes them (“Is this word like me?”), they encode it more durably than when processing it abstractly (“Is this word abstract?”). The self, in this framework, is a privileged node in cognitive architecture, a mental structure that confers processing advantages on anything connected to it.

IT-identity theory extends this logic to technological artifacts. People form identity relationships with their tools, experiencing technology not merely as useful but as self-expressive. A smartphone is not just a communication device; it becomes “my” phone, part of how I navigate and represent myself in the world. If this framework applies to AI assistants, then users with the strongest identity relationships should interact differently—more personally, more expressively, with more markers of self-involvement.

Cognitive offloading provided a third theoretical thread. When people delegate cognitive tasks to external tools—writing notes instead of memorizing, using calculators instead of mental arithmetic—they shift processing from internal to external systems. The decision to offload is driven partly by metacognitive judgments about one’s own cognitive capacity. If AI serves as a cognitive prosthesis, heavy users might be those who most readily see themselves as needing such support, a self-perception that should surface in their language.

| Feature Category | Example Features | Expected Relationship | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reference | I, me, my, mine | Higher → More engagement | Self-reference effect: self-related processing predicts deeper encoding |

| Direct address | You, your | Higher → More engagement | IT-identity: users who address AI personally form stronger tool relationships |

| Politeness | Please, thank you | Higher → More engagement | Relationship markers indicate affective investment in interaction |

| Complexity | Word count | Higher → More engagement | Proxy for task sophistication and cognitive investment |

II.B The Experimental Design

To test these expectations, I designed a temporal holdout validation study. The principle was simple: train on the past, test on the future. Specifically, I split the dataset at January 1, 2025—users whose first conversation occurred before this cutoff formed the training set, while users whose first conversation occurred after this cutoff formed the test set.

This design decision mattered more than it might appear. A naive split—randomly assigning users to train and test sets—would allow the model to “see” information about users it would later predict, because the same user’s early conversations might appear in training while their return status was measured in testing. By restricting the test set to genuinely new users who appeared only after the cutoff, I ensured that the validation measured true predictive power on users the model had never encountered in any form.

The feature sets included the identity markers described above: first-person singular pronouns (I/me/my), first-person plural pronouns (we/us/our), second-person pronouns (you/your), and politeness markers (please, thank you, appreciate). I also included structural features: word count, character count, question presence, and imperative detection. All features were extracted from users’ first conversations only, to simulate what would be known at the point of initial contact.

The classifier was logistic regression—simple, interpretable, and sufficient for the question at hand. For full methodological details, see MTH-001.2.

II.C The Results

The baseline model, using word count alone, achieved an ROC AUC of 0.757 on the held-out test set of new users. This single feature—how much someone typed in their first conversation—explained the majority of predictive variance.

Adding the full battery of identity markers, politeness indicators, and structural features raised the AUC to 0.769. The gain was 0.012—statistically detectable but substantively trivial. The gap is the sound of a hypothesis collapsing. Everything we thought would matter, didn’t.

Permutation importance analysis made the concentration visible. Word count accounted for approximately 96% of the model’s total importance. All identity features combined—every pronoun, every politeness marker, every signal of self-involvement that the literature suggested should matter—contributed roughly 4%.

The elaborate machinery of identity detection contributed almost nothing. What mattered was how much someone typed—a proxy, I came to believe, not for who they are, but for what they were trying to do.

We had built a sophisticated instrument to detect the texture of the soul; what we needed, it turned out, was a word counter.

II.D Why Identity Failed

The failure of identity markers demands explanation. Two frameworks help make sense of this null result.

The cognitive offloading literature suggests that the decision to use external cognitive tools is driven primarily by task demands and metacognitive assessment of those demands—not by stable personality traits or enduring self-perceptions. When faced with a task that exceeds working memory capacity, people reach for their notes, their calculators, their AI assistants. The reaching is situational, calibrated to the specific problem at hand. Users do not approach AI as an expression of who they are; they approach it based on what they are trying to do.

The metacognitive judgment is key. Before offloading, people implicitly assess: is this task within my capacity, or does it exceed it? The assessment depends on the task, not the self. A programmer might offload documentation lookup to AI while retaining core algorithm design internally. A writer might offload research while retaining voice. The boundary shifts with context. What remains constant is that offloading decisions are task-calibrated, not identity-expressive.

If offloading is task-driven rather than identity-driven, then identity markers should be weak predictors of return behavior—which is precisely what the data show. What predicts return is not self-involvement but task involvement: users with more complex tasks (as proxied by word count) have more complex needs, which bring them back for subsequent interactions. The prediction follows directly from the framework: task complexity creates cognitive load, cognitive load motivates offloading, and the accumulation of tasks creates the habit of returning.

A second framework inverts the expected relationship between expertise and self-focus. In the skill acquisition literature, the development of automaticity is associated with reduced conscious self-monitoring. Expert performers attend less to their own processes; their actions become proceduralized, requiring less explicit attention. The tennis player no longer thinks about grip; the driver no longer narrates lane changes; the expert AI user no longer prefaces prompts with conversational padding. If heavy AI users have developed expertise in AI interaction, their reduced self-reference may signal efficiency, not disengagement.

This inversion matters because it reframes what we measure when we measure identity markers. We assumed that self-reference indexes engagement—that the pronouns “I” and “me” mark cognitive investment. But self-reference may instead index uncertainty, the novice’s need to situate themselves in an unfamiliar context. Expertise strips that need away. The absence of self-reference, paradoxically, may mark deeper integration.

For the peer-reviewed literature underlying these frameworks, see LIB-002.

III. The Inverted Self-Reference

III.A The Discovery

The predictive failure of identity markers was surprising. What I found when examining power users descriptively was stranger still.

I segmented users into five tiers based on their total conversation count: one-shot users (single conversation), light users (2-4 conversations), moderate users (5-20 conversations), heavy users (21-99 conversations), and power users (100+ conversations). The distribution was sharply skewed: 91.2% of users were one-shot, while power users constituted just 0.1% of the population—but accounted for 26.4% of all conversations.

Across nearly every linguistic marker, the expected pattern was inverted. Power users showed lower rates of first-person plural language than one-shot users—despite moderate users showing the highest rates. Within power users, longitudinal analysis revealed declining self-reference and declining politeness as experience accumulated.

| Marker | One-Shot | Moderate | Power | Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-person plural (we/us) | 0.032 | 0.053 | 0.021 | Power < One-shot |

| Second-person (you/your)* | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.29 | Heavy users lowest |

| Within-user I-rate change | — | — | -4.2% | Early → Late |

| Within-user politeness change | — | — | -20.4% | Early → Late |

The pattern was not merely null but reversed. The users with the deepest quantitative engagement with AI showed the linguistic signatures we would associate with lower, not higher, personal investment.

III.B Explaining the Inversion

Two complementary explanations account for this paradox.

First, the skill acquisition literature establishes that expertise is associated with efficiency and automaticity. As people develop skill in a domain, they strip away unnecessary processing. Musicians no longer consciously think about finger placement; drivers no longer narrate their lane changes; writers no longer preface every sentence with qualifications. The progression follows a predictable arc: declarative knowledge becomes procedural, explicit becomes implicit, effortful becomes automatic.

Expert AI users, by this logic, have proceduralized their interactions. They know what works. They have developed efficient prompting strategies—knowing when to be terse, when to elaborate, when to request clarification. The pronouns and politeness markers that characterize novice interactions are cognitive scaffolding that experts no longer require. “Please help me understand…” becomes simply the question. “I was wondering if you could…” becomes the request unadorned.

The efficiency hypothesis predicts precisely the pattern we observe: as usage increases, linguistic markers decrease. Each conversation teaches the user something about effective communication with AI. The lessons accumulate. By the hundredth conversation, the elaborate preambles of novice prompts have been stripped away, replaced by direct task specification.

Second, research on self-focused attention suggests that conscious self-monitoring can actually impair skilled performance. When experts attend to their own processes—when they think about themselves as they perform—performance degrades. The phenomenon is familiar to athletes as “choking” under pressure. Analyze your swing, and you lose your swing. Monitor your speech, and you stumble. Self-focus redirects cognitive resources from execution to evaluation, disrupting the automaticity that expertise confers.

Power users’ reduced self-reference may not indicate lower engagement but rather the absence of performance anxiety, the comfort of automaticity that comes from hundreds of prior interactions. They are not thinking about whether they are communicating well; they are simply communicating. The absence of “I” is not absence of investment but absence of self-doubt.

The pronouns and politeness markers, on this account, are not signals of investment. They are filler—the conversational equivalent of throat-clearing. Experts don’t clear their throats. The power users who show the lowest self-reference are not the least invested; they are the most fluent.

For the skill acquisition and expertise literature, see LIB-002.

III.C The Pivot

The failure of identity markers—predictively and descriptively—forced a methodological pivot. If hand-crafted linguistic features could not distinguish who would return, perhaps the semantic content of what users explored could.

The pivot shifted from hypothesis-driven feature engineering to embedding-based exploration. Rather than counting pronouns, I would map the topics users traversed in high-dimensional semantic space. Rather than asking how users expressed themselves, I would ask what they explored.

If who you are does not predict engagement, perhaps what you explore does.

IV. Semantic Diversity

IV.A The Embedding Approach

Semantic embeddings represent text as points in high-dimensional space, where distance corresponds to semantic dissimilarity. Two sentences about cooking cluster near each other; a sentence about cooking and a sentence about astrophysics sit far apart. By mapping each user’s conversations into this space, I could measure something word count could not capture: topical breadth.

For each user with sufficient interaction history, I computed semantic diversity as the spread of their conversation embeddings—the degree to which their interactions ranged across different topics rather than clustering in a single domain. A user who asked about cooking every time would have low semantic diversity; a user who asked about cooking, then philosophy, then car repair, then music theory would have high semantic diversity.

This measure captures something distinct from task complexity. A user could type lengthy, complex prompts about a single domain (high word count, low semantic diversity) or brief prompts across many domains (low word count, high semantic diversity). The two dimensions are orthogonal.

For full methodological details on the embedding approach, see MTH-001.3.

IV.B The Key Finding

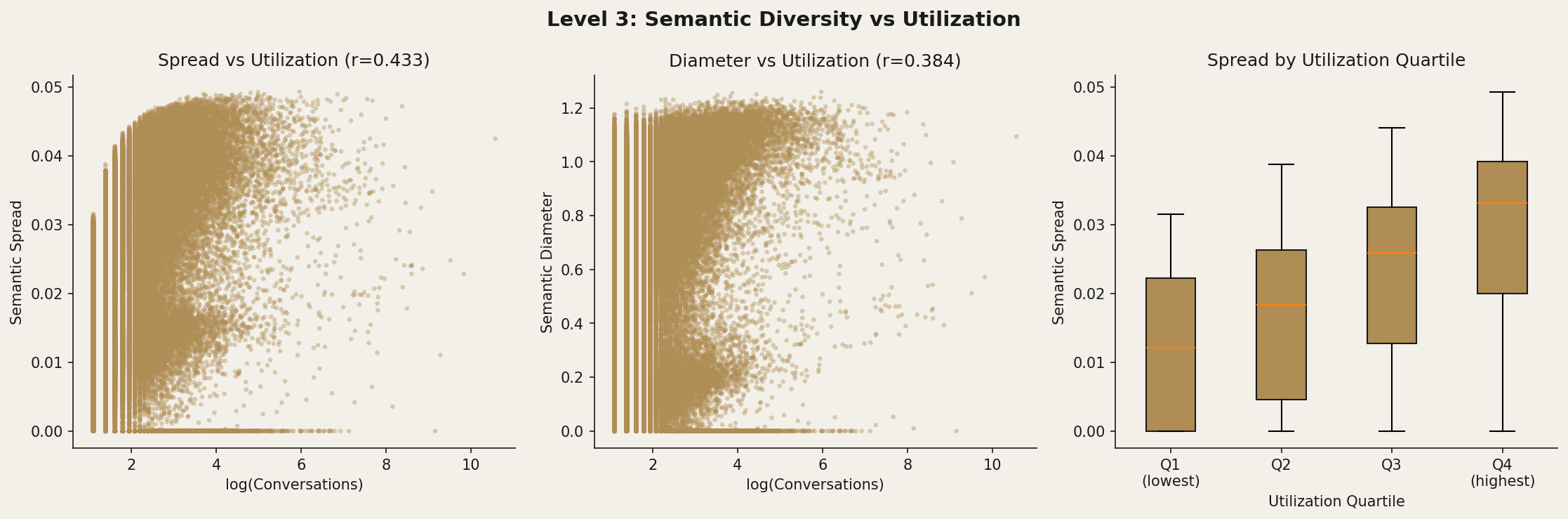

Semantic diversity correlated meaningfully with sustained engagement. Among users with sufficient interaction history, the correlation between semantic spread and log-utilization (conversations over time) was r = 0.433 (p < 0.0001). First-turn embeddings alone explained approximately 28% of variance in log-utilization (R² = 0.284)—better than hand-crafted features but far from deterministic. Topic-level diversity, measured as entropy across BERTopic clusters, showed a weaker but still significant correlation (r = 0.25).

A correlation of 0.43 is not destiny, but it is signal. In a dataset of millions, where most relationships wash out to noise, this one persists. Users who wander, stay.

This correlation is not a statistical artifact of word count. Users who explored more diverse topics—who ranged across domains rather than repeating questions within a single area—showed higher sustained engagement with the platform, controlling for how much they wrote.

The implication is striking: topical breadth, not depth in any single domain, predicts who stays.

IV.C Curiosity as the Engine

The curiosity literature offers a framework for understanding this pattern. Curiosity is not a unitary drive but a cognitive state triggered by specific conditions: information gaps that are neither too small (boring) nor too large (overwhelming), but intermediate—tractable unknowns that promise learnable answers. The feeling of “I could figure this out” is the signature of curiosity; the feeling of “I already know this” or “I could never understand this” is its absence.

Curiosity creates a positive feedback loop with learning. Experiencing learning progress triggers intrinsic reward, which motivates further exploration, which produces more learning, and so on. The loop is self-sustaining: each small discovery creates appetite for the next. Users who explore diverse topics encounter more intermediate information gaps, sustaining the curiosity that drives continued engagement. They never exhaust the supply of tractable unknowns because each domain they enter exposes new ones.

Semantic diversity, in this framework, is a behavioral signature of the curiosity phenotype. It does not measure a personality trait but a pattern of interaction: the tendency to traverse new domains rather than repeating established ones. Users who explore are users who stay. The correlation is not between engagement and any single topic but between engagement and the pattern of moving between topics.

This interpretation connects to recent work on novelty, complexity, and incongruity as drivers of exploratory behavior. Novel stimuli attract attention; moderately complex stimuli sustain it. The optimal zone—not too familiar, not too foreign—is where curiosity thrives. AI systems that expose users to adjacent topics—that surface related questions or unexpected connections—may tap into these drivers. They position users in the intermediate zone, where curiosity is kindled.

The contrast with task completion is instructive. A user who comes to AI with a specific problem, gets the answer, and leaves has completed a task but has not necessarily triggered curiosity. The transaction is closed; there is no intermediate gap, no appetite for what comes next. A user who comes with a question, receives an answer that suggests two more questions, and follows those threads has entered the curiosity loop. Duration becomes a byproduct of exploration, not an end in itself.

The data suggest that exploration, not task completion, predicts sustained use. The curious user is not the one who solved the most problems but the one who discovered the most new ones.

See LIB-002 for the underlying peer-reviewed work.

IV.D Design Implications

Current AI systems are largely optimized for task completion. The user asks a question; the system answers it. Efficiency is the metric: minimize tokens, maximize accuracy, complete the task. The implicit model is the user as problem-solver, approaching AI with a specific need and departing when the need is met. Design efforts focus on reducing friction: faster responses, cleaner interfaces, fewer clicks to resolution.

The semantic diversity findings suggest an alternative model: the user as explorer. If exploration predicts sustained engagement, then interfaces that surface adjacent topics—“You asked about X; here’s something related you might not know”—may cultivate the curiosity that keeps users returning. Such features would not solve problems faster; they would generate new ones. They would position users in the intermediate zone where curiosity ignites.

The analogy to physical exploration is instructive. A good hiking trail does not simply transport you from trailhead to summit; it exposes you to vistas that make you want to explore further. A good bookstore does not simply deliver the book you came for; it surrounds you with books you did not know you wanted. Current AI design is more like a taxi: it gets you where you asked to go, then asks if you’d like a receipt. AI optimized for exploration would exceed the transaction, surfacing connections that extend the journey.

This is speculative. The data are correlational, and I cannot determine whether semantic diversity causes sustained engagement or whether curious users select into both behaviors. Nor do I know whether designing for exploration would increase healthy engagement or merely extend time-on-platform without cognitive benefit. An interface that generates rabbit holes might cultivate learning or might merely distract; the difference is not obvious from usage data alone.

What the data do suggest is that duration is a consequence of curiosity, not a driver of it. Users who stay are not those with the longest sessions but those with the widest-ranging questions. Understanding sustained engagement—or designing for it—may require attending to topical breadth, not elapsed time.

V. Concerning Sessions

V.A The Safety Framing

As AI systems become integrated into daily life, platforms increasingly implement risk detection based on usage patterns. The logic is intuitive: users who interact with AI for extended periods, with high intensity, in the late-night hours, may be at risk—of dependence, of isolation, of substituting AI for human connection.

The impulse is not new. The nineteenth century panicked over “reading mania”—young women, it was feared, were losing themselves in novels. The twentieth century pathologized television hours. Each era identifies a technology of absorption and worries that duration signals dysfunction. AI is the current candidate.

Duration-based flags have become a standard tool in the platform safety toolkit. The intuition is not unreasonable. Some extended AI use likely does reflect distress. But what is the base rate? How many users flagged by duration-based criteria are actually concerning?

V.B Our Operationalization

To investigate, I operationalized “potentially concerning sessions” using four criteria: session span exceeding 6 hours (elapsed time from first to last message), turn density exceeding 2 turns per hour (active engagement, not idle tabs), maximum internal gap under 60 minutes (sustained interaction, not abandoned sessions), and total turns exceeding 30 (substantial interaction volume).

| Criterion | Threshold | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Session span | > 6 hours | Extended duration suggests sustained involvement |

| Turn density | ≥ 2 turns/hour | Active engagement, not passive tab |

| Max internal gap | < 60 minutes | Sustained attention, not interrupted |

| Total turns | ≥ 30 | Substantial interaction volume |

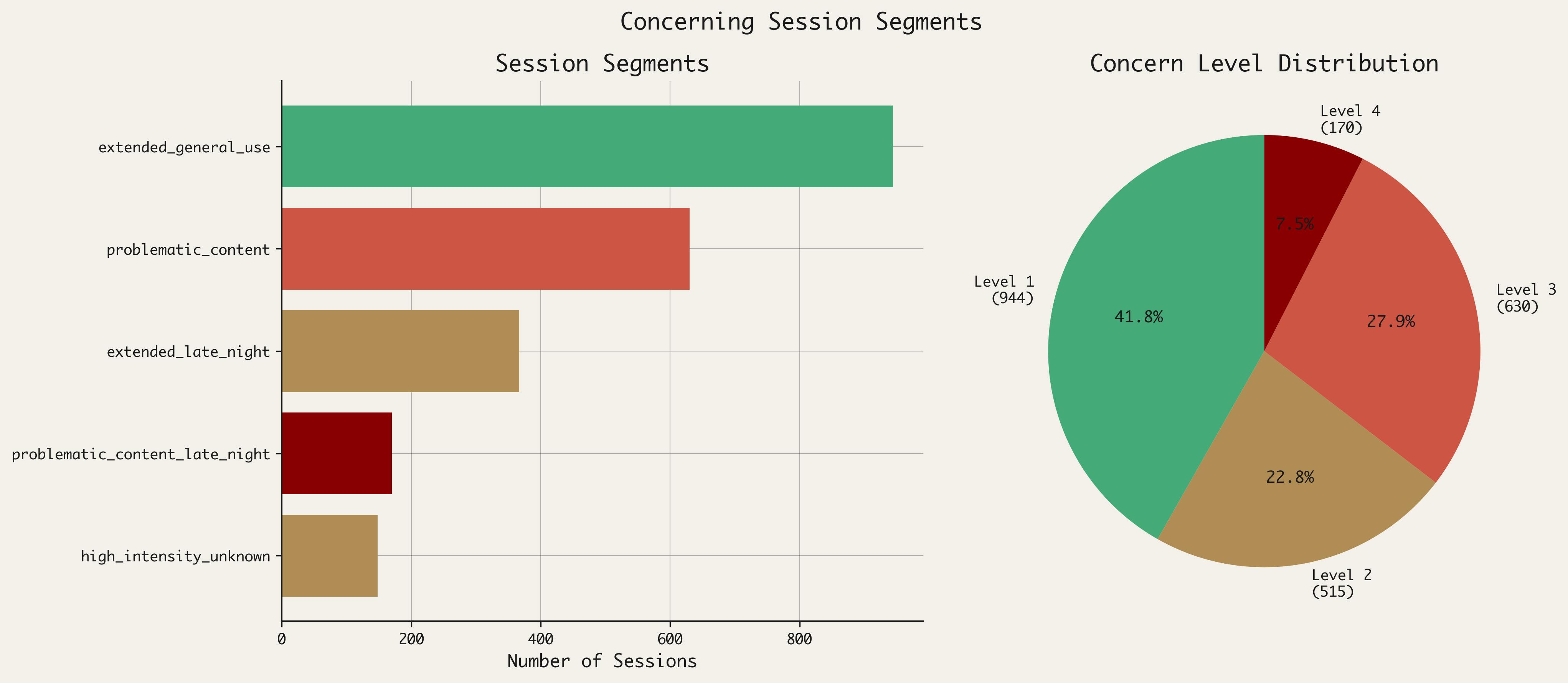

Applying all four criteria, 2,259 sessions qualified as potentially concerning—0.36% of all sessions in the dataset. These are the sessions that duration-based detection systems would flag.

For full methodology, see MTH-001.5.

V.C The Segment Taxonomy

The 2,259 potentially concerning sessions were not a homogeneous group. When I classified them by content and temporal characteristics, a taxonomy emerged.

The largest segment, accounting for 41.8% of concerning sessions (944 sessions), was extended general use—sessions with long duration but no toxicity indicators and no late-night timing. These are users engaged in sustained, benign interaction: working through complex problems, exploring topics at length, treating AI as a thinking partner over an extended period.

The second segment, accounting for 27.9% (630 sessions), involved problematic content—elevated toxicity scores without late-night clustering. These sessions included concerning language but occurred during normal hours and often represented isolated incidents rather than patterns.

The third segment, 16.2% (367 sessions), was extended late-night use without toxicity—users interacting during the midnight-to-6am window for extended periods, but without concerning content. Many may reflect shift workers, insomniacs, or users in different time zones, rather than distress.

The fourth segment, 7.5% (170 sessions), combined multiple risk indicators: elevated toxicity, late-night timing, and in many cases, repeat behavior from the same users. This is the segment that most warrants concern. (Note: The fifth segment, representing 6.6% of concerning sessions (148 sessions), was of medium-level concern.)

The plurality matters. When nearly half of flagged sessions are benign exploration, the flag has lost its meaning—or rather, it has acquired a new one. It no longer marks risk; it marks curiosity mistaken for pathology.

Only 7.5% of sessions meeting ‘concerning’ criteria showed the pattern we’d most worry about: toxic content, late-night timing, and repeat behavior. The plurality—nearly half—were simply extended, engaged use with no risk indicators.

V.D The Base Rate Problem

The segment taxonomy illustrates a fundamental problem with duration-based risk detection: the base rate problem.

The true rate of concerning behavior is low. Even among flagged sessions, only 7.5% met multiple risk criteria. Any detection system will produce more false positives than true positives. A flag that is 80% accurate sounds reliable, but if concerning cases constitute 1% of flagged sessions, then 80% accuracy still means that false positives outnumber true positives by a wide margin. The test catches most of the concerning cases, but it also catches many more non-concerning ones.

The phenomenon is well-documented in medical screening, criminal justice, and fraud detection. When you search for rare events using imperfect indicators, you find mostly false alarms. The intuition that “extended use is concerning” may be correct for some cases, but when extended use is far more common among the curious than among the distressed, the indicator becomes misleading.

We design detection systems hoping to find the suffering. Instead, we find the searching—and in labeling their behavior “concerning,” we reveal our assumption that depth of engagement must signal something wrong. The curious become suspects; the algorithm, unable to distinguish fascination from desperation, flags both.

This is not a criticism of any specific platform’s policies, which I have not evaluated. It is a structural observation about duration-based detection. When base rates are low, even accurate tests mislead. Algorithmic risk assessment, applied to rare behaviors, will predominantly flag non-concerning cases. The algorithm is not wrong; it is doing what it was designed to do. The problem is that what it was designed to detect is rare, and what it predominantly captures is benign.

The consequence is that duration-based detection may pathologize the curious—flagging the power users whose semantic diversity and sustained engagement reflect intellectual exploration, not distress. The very users whose behavior we might want to encourage—deep engagement, sustained exploration, genuine curiosity—become the ones most likely to trigger concern. The system mistakes depth for dysfunction.

See LIB-002 for the underlying peer-reviewed research.

V.E What Actually Distinguishes Risk

The highest-concern segment—the 7.5% combining toxicity, late-night timing, and repeat behavior—differed from other segments on specific dimensions. They showed elevated toxicity ratios (sessions with greater than 50% toxic conversations). They clustered in the late-night hours, with session starts between 10 PM and 4 AM. And they showed persistence: the same users appearing in multiple concerning sessions over time.

Content and pattern, not duration, distinguished this segment. The lesson is not that extended AI use is uniformly safe. The lesson is that our instruments for detecting distress are blunt, and that the categories we impose—“concerning,” “at-risk,” “problematic”—say as much about our anxieties as about the users we flag. Duration measures time, not suffering. The two are not the same.

VI. Model Upgrades

VI.A The Question

If engagement is driven by task completion—and if word count’s predictive dominance suggests users return when AI solves their problems—then model capability should matter. Better models solve more problems. Better models should produce more return.

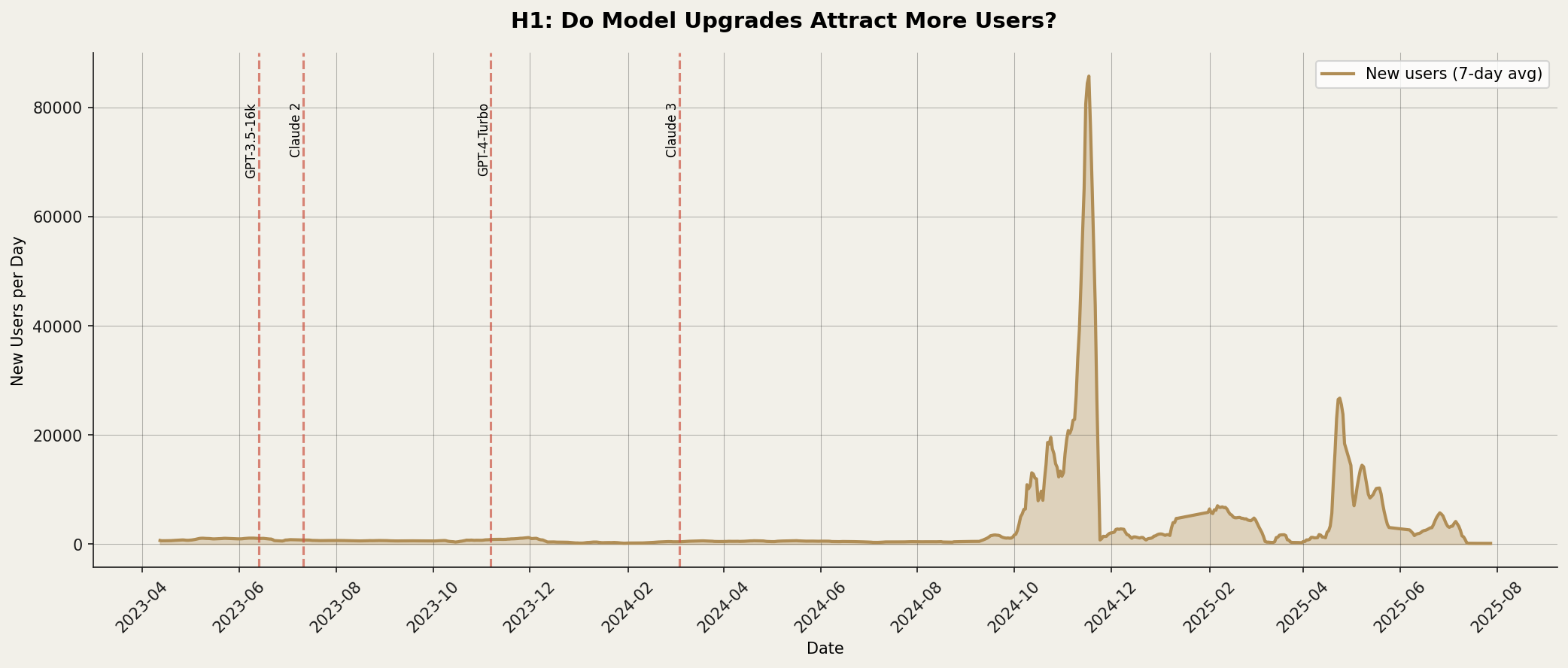

The WildChat dataset spans a period of rapid model improvement, from GPT-3.5 through GPT-4 to GPT-4-Turbo. Each upgrade offered improved capabilities: longer context windows, better reasoning, fewer hallucinations. If capability drives engagement, these transitions should produce measurable effects on user behavior.

VI.B The Design

I treated each major model upgrade as a natural experiment, analyzing metrics before and after the transition. The analysis addressed five hypotheses:

| ID | Hypothesis | Prediction | Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Upgrades attract users | New user count increases post-upgrade | Daily new users |

| H2 | Upgrades increase return rate | Return rate increases post-upgrade | 60-day return rate |

| H3 | Upgrades increase diversity | Topic diversity increases | Semantic spread |

| H4 | Upgrades deepen conversations | Turns per conversation increase | Mean turns |

| H5 | Upgrades increase satisfaction | Session length increases | Session duration |

For full methodology on the interrupted time series design, see MTH-001.4.

VI.C The Findings

The results were mixed, with stronger effects on attraction than on behavior.

H1 (attraction) showed the clearest support: model upgrades were associated with increases in daily new user counts, particularly around major transitions like GPT-4-Turbo. The upgrades drew attention; users arrived to try the new capabilities.

H2-H5 showed weaker effects. Return rates, semantic diversity, conversation depth, and session length did not show consistent, substantial changes following upgrades. Users who arrived continued to behave much as users had before. The capability improvements did not transform interaction patterns.

| Hypothesis | Prediction | Result | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Attract users | More new users | Supported | Visible increase post-upgrade |

| H2: Increase return | Higher return rate | Limited | No consistent pattern |

| H3: Increase diversity | Broader topics | Limited | No consistent pattern |

| H4: Deepen conversations | More turns | Limited | No consistent pattern |

| H5: Increase satisfaction | Longer sessions | Unclear | Data limitations |

VI.D Interpretation

The pattern suggests that model upgrades attract but do not transform. Users notice new capabilities and arrive to investigate. But their fundamental interaction patterns—how often they return, how broadly they explore, how deeply they engage—remain stable. A better calculator does not change when you reach for it. Neither, it seems, does a better chatbot.

This connects to the cognitive offloading framework. Once users establish patterns for delegating cognitive tasks to AI, those patterns persist. The habit of reaching for AI when facing certain problems—and not reaching for it in other contexts—may be stickier than the capabilities of any particular model. Tool quality is necessary but not sufficient; usage patterns, once established, have their own inertia.

VII. Conclusions

VII.A The Emerging Picture

Four findings emerged from this analysis, each unexpected, each pointing toward a common framework:

Task over identity. What users ask—as proxied by word count—predicts engagement far better than who they are, as measured by identity markers. Users approach AI with problems, not personalities. The decision to return is driven by task demands, not self-conception.

Curiosity as phenotype. Semantic diversity marks the curious user, whose exploration of varied topics correlates with sustained engagement. Duration follows curiosity; power users are not those with the longest sessions but those with the widest-ranging questions.

Duration is a poor proxy. Most sessions flagged as “concerning” by duration-based criteria are benign. Extended use more often reflects exploration than distress. Content and pattern, not elapsed time, distinguish genuine risk.

Capability matters, habits matter more. Model upgrades attract new users but do not transform behavior. Usage patterns, once established, persist across capability improvements.

VII.B Theoretical Integration

Cognitive offloading provides a unifying lens for these findings.

The offloading framework posits that people use external tools—notes, calculators, AI—to reduce cognitive load. This is not new. Socrates worried that writing would weaken memory; he was not entirely wrong. What is new is the scale: billions of people are reaching for the same tool, delegating the same classes of cognitive work. The prosthesis has become infrastructure.

The decision to offload is task-driven: when the task exceeds internal capacity, we reach for support. If AI use is primarily task-driven, then identity markers—which capture who the user is—should poorly predict engagement. This is what the data show. The identity hypothesis assumed that AI use expresses something about the self; the offloading framework suggests it expresses something about the task.

The framework also predicts that offloading becomes automatic with practice. As users proceduralize their AI interactions, they strip away the conscious self-monitoring that characterizes novice behavior. Expert users need not remind themselves that they are using AI; the reaching becomes habitual, like reaching for a calculator when multiplying large numbers. The action is not about identity but about getting the job done. This predicts reduced self-reference among power users—again, what the data show.

The link between semantic diversity and sustained engagement fits the framework as well. Offloading enables exploration. When cognitive load is externalized to AI, capacity is freed for traversing new domains. A user who delegates factual lookup to AI can pursue more ambitious questions; a user who delegates prose drafting can explore more topics. Offloading is not a substitute for thinking but a multiplier of cognitive reach. Users who offload effectively can explore more broadly; the tool enables the curiosity rather than substituting for it.

The curious user, in this framing, is not the one who thinks less but the one who thinks about more. The AI handles the cognitive infrastructure—the facts, the phrasing, the organization—while the user ranges across domains. Semantic diversity is a signature of this expanded reach: the user who offloads routine cognition to AI explores topics that would otherwise exceed their bandwidth.

Finally, the stickiness of usage patterns despite model upgrades reflects the persistence of offloading habits. Once users establish routines for when and how to delegate cognitive tasks, those routines endure. The tool improves; the usage patterns remain. The habits of reaching, once formed, are stable.

Human-AI interaction may be less about who we are and more about what problems we carry. The AI is a cognitive prosthetic; we reach for it when the task exceeds our internal capacity. Those who reach for diverse tasks develop a habit of reaching. Duration follows curiosity—and curiosity, it seems, is the engine of sustained engagement.

VII.C Implications for AI Safety

Three practical implications follow from these findings:

Recalibrate risk detection. Duration-based flags produce predominantly false positives. Platforms relying on session length to identify concerning users will mostly identify the curious. Risk detection should incorporate content signals and behavioral patterns, not merely elapsed time.

Design for curiosity. If exploration predicts healthy engagement, interfaces might cultivate it—surfacing adjacent topics, suggesting related questions, exposing users to domains beyond their initial queries. This is speculative but tractable: the data suggest what to optimize for, even if the optimal design remains to be discovered.

Monitor content, not time. The concerning session analysis identified content (toxicity), timing (late-night clustering), and persistence (repeat concerning sessions) as distinguishing factors. These are harder to measure than duration but more meaningful as risk signals.

VII.D The Open Question

One limitation shadows this analysis: causality. I cannot determine whether AI use shapes curiosity or merely reveals it. Do semantically diverse users become more curious through their AI interactions, exploring domains they would not have encountered otherwise? Or does semantic diversity simply reflect pre-existing curiosity, with the tool as a window onto a trait that would express itself regardless?

The distinction matters. If AI cultivates curiosity, the tool has developmental potential—a capacity to expand users’ intellectual horizons. A student who begins with narrow questions might, through AI interaction, discover adjacent domains they never knew existed. The tool would be not just useful but formative. If AI merely reveals curiosity, the tool is a diagnostic instrument, useful for identifying traits but not for fostering them. The curious would use it curiously; the incurious would not be changed.

The answer is probably some mixture. Selection and development often coexist: curious people select into exploratory behavior, and exploratory behavior develops curiosity. The feedback loop runs in both directions. But the balance matters for design: if development dominates, investment in features that expose users to novelty would be warranted; if selection dominates, such features might be ignored by the incurious and unnecessary for the curious.

There is something uncomfortable in not knowing. We would prefer a clean story: AI cultivates curiosity, or AI attracts the curious. The muddled truth—that selection and development intertwine, that the tool both reveals and shapes—resists the clarity we seek. Perhaps that discomfort is itself informative. The mind resists being measured, even as it reaches for instruments to measure itself.

Longitudinal data could distinguish these accounts. Track individuals over months and years. Observe whether semantic diversity increases with use, or whether it remains stable—a stable phenotype rather than a developable skill. Measure whether exposure to adjacent topics shifts subsequent exploration, or whether users stay in their lanes regardless of what the tool surfaces. Such data do not yet exist in sufficient depth; their collection would advance both theory and practice.

For now, what I have is a static portrait of a dynamic process: humans meeting machines, carrying their problems, and sometimes discovering new ones. The curious explore and stay; the explorers become curious. Which comes first remains uncertain. That they come together seems clear.

VIII. References

For the peer-reviewed literature on cognitive offloading, self-reference effects, skill acquisition, curiosity, and base rate fallacy that informs this dispatch, see LIB-002.

Data Source

WildChat Dataset, Allen AI Institute

Citation

Zhao, W., Ren, X., Hessel, J., Cardie, C., Choi, Y., & Deng, Y. (2024). WildChat: 1M ChatGPT Interaction Logs in the Wild. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2024). https://openreview.net/forum?id=Bl8u7ZRlbM