Semantic Cartography

Challenging our Semantic Associations Through Games with AI

I. The Information-Cognition Loop

Cognition is molded by our information environment.1 In fact, current theories of intelligence suggest that human uniqueness emerged through evolutionary improvements in our information processing abilities.2 Of the various types of information encoded by our brain, semantic memory is the system responsible for the storage of semantic categories—categories of natural and artificial concepts, from concrete objects like fruits and vehicles to abstract notions like justice3,4—and is bidirectionally sculpted by the medium of information itself: language.1 The very act of learning to read and write rewires the brain,5 and written language comprehension—which draws upon semantic memory representations4—involves many cognitive processes: recognizing individual written words, understanding how words relate to each other, how they fit together in sentences, and how context constrains interpretation.6

This bidirectional shaping correlates with both human potential and downfall: genius and madness. Individuals proficient in wielding information technologies—art, music, literature—for creative, generative processes are characterized by having a more flexible semantic memory structure—higher connectivity and shorter distances between concepts—which facilitates connecting remotely associated concepts to form new ideas.3,7 The ability to generate numerous and original associative combinations predicts creative ideation performance, independent of the ability to retrieve original associations.8 In turn, information exposure also carries the potential to turn the mind upon itself. Psychosis, a feature of which are delusions—fixed beliefs in falsehoods—carries features of the information environment; signs of psychosis over the decades resemble the technologies of the era.9,10,11 More recently, reports of AI-induced delusions are emerging in clinical literature, with psychiatrists documenting cases where chatbot interactions appear to reinforce or generate psychotic thinking in vulnerable individuals.12,13 Just as humans exposed to biased information sources absorb those biases into their own judgment, humans who interact with biased AI systems subconsciously absorb the biases in their outputs, supporting the emergence of a feedback loop in which we acquire new patterns of thought from our information environment.14,15 These effects have a direct consequence on the quality and quantity of life itself, as a growing body of literature demonstrates that certain cognitive faculties—including semantic fluency and verbal memory—are associated with healthier aging trajectories.16

Thus, measurements of cognition may be an important marker of fitness: our cognition underlies our ability to successfully overcome specific challenges in our environment. While certain features, like personality as measured by instruments such as the Big Five Inventory (BFI) or NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R), exhibit substantial heritability and relative stability over time,17,18 features related to knowledge and memory are more dynamic—they change with experience and are shaped by context.1 Since knowledge and memory are semantic, they are shaped by experience. As experience cannot be fully accounted for in a laboratory setting, the ecological validity of laboratory-based cognitive measures remains limited.19 Questions like “Given my personality and cognitive profile, what books should I read? What kind of meditation should I do? What kind of profession will protect my mental health?” remain unanswerable with traditional empirical techniques.

The aim of INS-001 - the first family of instruments at Phronos.org - is to test the hypothesis that we can use the tools of AI to measure the very dimensions of cognition being reshaped by AI.

II. The Atomic Unit of Thought

Free association tasks prompt participants to generate words that come to mind in response to cues; those cues can be visual and/or verbal.20 These responses have been found to represent the associative knowledge of words we possess at an implicit level.21 Free association has been studied for nearly 150 years, largely viewed as a window into the unconscious mind—an idea later expanded upon by psychoanalysts, and followed by cognitive scientists who developed formal tests of association.8 Word associations illuminate how concepts are interconnected within human cognition, providing essential insights into the thought processes that AI systems are now reshaping.22

Although the ultimate goal is to deconstruct our cognition from chat logs and AI-enabled workspaces, those datasets represent complex sequences of behaviors and chains of reasoning, which have not been robustly studied in either the qualitative or quantitative literature. Instead, atomic units of cognition—words and tokens—have been exhaustively studied, with rapid growth over the past two decades in the field of natural language processing and computational semantics.1 This makes them tractable starting points for measurement.

Within semantic analysis, there are several research traditions that enable comparison between human and AI cognition:

Associative approaches use free association tasks to prompt people to generate words that come to mind in response to cue words, viewing these associations as windows into memory structure and retrieval processes.8

Distributional semantics is based on the idea that it is possible to understand the meaning of words by observing the contexts in which they are used—“you shall know a word by the company it keeps.” Word meanings are similar to the extent that the contexts in which they are used are similar.23

Network models of semantic memory are built from free associations by connecting cue words to their responses, resulting in complex network structures of human conceptual knowledge in which words derive meaning through relationships to other concepts. Unlike model-level embedding-based metrics, which often operate as opaque vector-space measures, network-based methodology offers interpretable structures where nodes represent concepts and edges capture associative strength.15

Distributional and network models require aggregate statistics—either on individuals or on text corpora—which complicates individual-level inference due to the ecological fallacy: conclusions drawn about groups may not apply to any particular individual within them.24 Associative approaches offer the opportunity to retain individual-level information, so that we can ultimately make individual-level claims (of the form, “Since you scored X, this means Y about you.”). This application has been demonstrated in creativity research, where individual differences in semantic memory network structure predict creative thinking ability.3,8

III. The Core Construct: Semantic Divergence and Fidelity Under Constraint

Amongst the repertoire of associative tasks that cognitive scientists have studied, there are two broad classes: unconstrained and constrained.8 In an unconstrained association exercise, a participant might be asked to generate words that come to mind in response to a cue word, with no restrictions on the type or number of responses;20 or to list all the alternative uses for a common object, as in the classic Alternative Uses Task;25 or to name words that are as different as possible from each other, as in the Divergent Association Task.26 In a constrained exercise, the participant might be asked to identify a word that connects three otherwise unrelated words, as in the Remote Associates Test;27 to generate words within a specific semantic category, as in verbal fluency tasks;8 or to produce associations that fit a specific task constraint or requirement.8

The associative theory of creativity posits that what distinguishes more creative people is their capacity for association—their ability to make new connections between seemingly unrelated concepts stored in memory.27,3,8 Creative people can make such novel associations due to their structure of memory: whereas a less creative person has strong connections between common concepts and weak connections between uncommon concepts, a highly creative person has connections of similar strength between both, facilitating the bypass of conventional associations to make novel, remote associations.8 More creative people search through semantic space more fluently and make more distant semantic associations, possibly because they possess a more richly connected semantic memory network.3 Visual artists spontaneously produce more remote associations than scientists or comparison groups—potentially due to a more interconnected semantic memory network structure.28 Notably, these were visual artists without special linguistic training; it is remarkable that they exhibited such pronounced word association ability compared to intelligence-matched scientists and comparison participants. This suggests that semantic network structure varies systematically across creative domains—and that word association tasks can detect these differences.

To devise a test of one’s associative skills against AI, however, we had to consider that AI has the ability to be infinitely divergent: with vast internet-scraped corpora as its training ground, an LLM may be able to generate associations that are far more divergent than humans. Indeed, LLMs trained on internet text produce free association norms that differ systematically from human responses, often generating more unusual or contextually varied associations.21 Constraining the task not only bounds the solution space, but it also reflects current challenges with human-AI interaction. Since LLMs are probabilistic systems that predict the most likely next token given context,21 they may struggle in optimization problems that require satisfying multiple constraints simultaneously; a multi-word association task can be modeled as such an optimization problem, framed as identifying the minimal spanning set between two words on a graph where nodes represent words and edges are weighted by semantic distance.

The set of words that represents a concept or pair of concepts can be rated by their divergence—how far they spread from each other in semantic space, measured computationally as semantic distance.29 In real-world scenarios, an individual does not usually free associate, unless perhaps in brainstorming sessions or free association games, like Codenames or Taboo. Even in these rare circumstances, the set of free associations are evaluated through social normalization: can the associations communicate a latent thought? The communicability of associations depends on shared semantic structure between communicators; research using cooperative word games has shown that human communicators rely on both associative and distributional semantic knowledge to generate clues that partners can successfully interpret.1 Thus, we can operationalize fidelity by (1) how well it allows signal recovery of the anchor-target words and/or (2) how well another intelligence—human or artificial—is able to recover the seed words from the clues.

These dual capacities—of divergent thinking and of high-fidelity communication—are precisely what AI may be challenging through cognitive offloading. Cognitive offloading refers to the use of physical action or external tools to alter the information processing requirements of a task, reducing cognitive demand.30 When individuals habitually delegate cognitive tasks to external systems, they may reduce opportunities to exercise and maintain these capacities.31 A 2025 study of 666 participants found a significant negative correlation between frequent AI use and critical thinking abilities, mediated by the tendency to delegate cognitive tasks to external tools.32

AI interactions are primarily lexical - through prompt-response interactions - and represent layered, complex reasoning steps that are difficult to measure and experimentally control. To identify a behavior that may be at risk of cognitive offloading to AI, I hypothesize that a semantic association task may provide a starting point, where AI and humans can be compared and where performance is measurable.

IV. Two Instruments, Two Constraint Types

To test this hypothesis, we have developed two instruments: INS-001.1 (Signal) and INS-001.2 (Common Ground).

INS-001.1: Signal

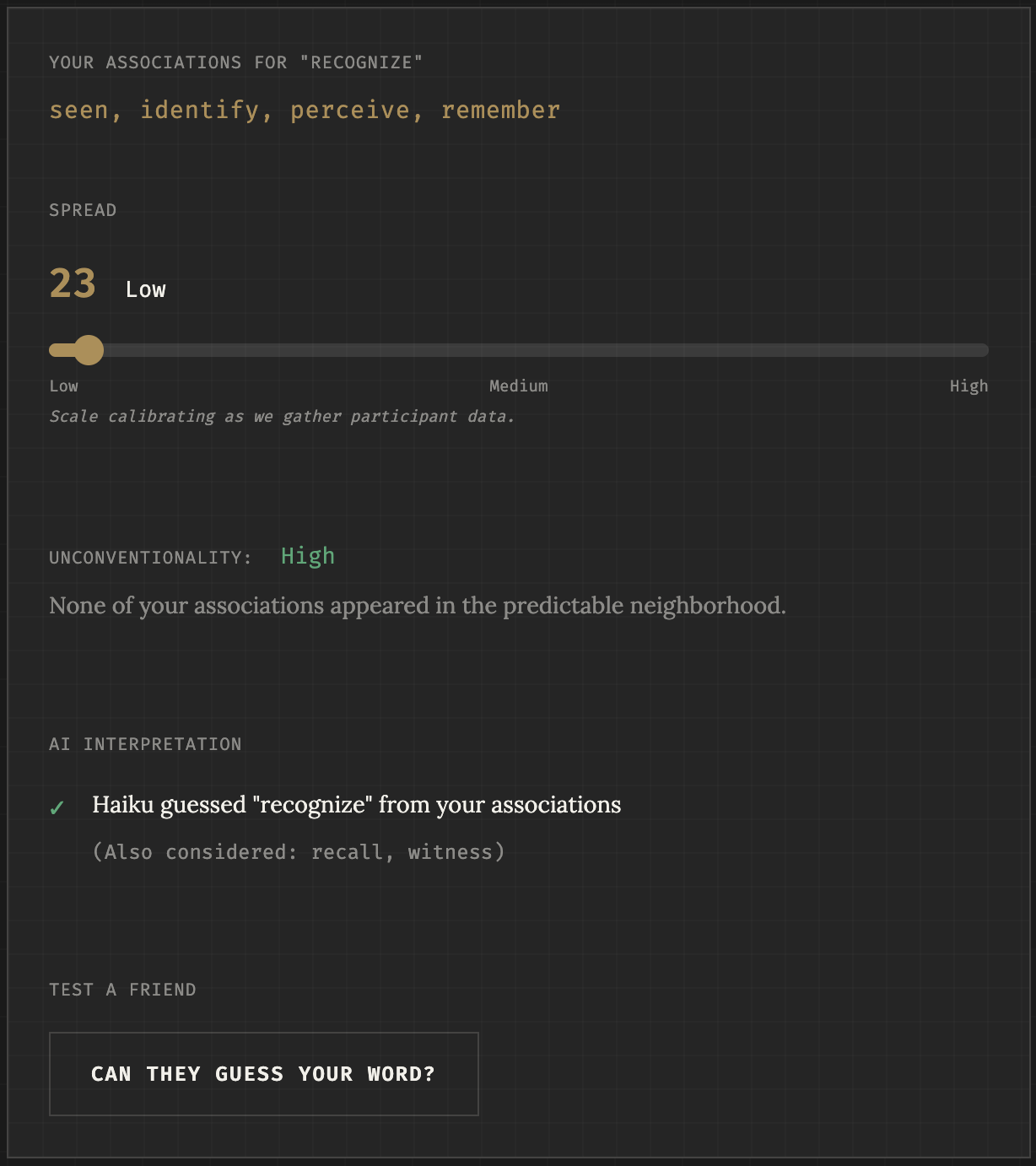

In this task, the participant generates associations that are associated with a single concept. They can choose their own anchor concept, or ask for a suggestion. They may submit up to 5 associations, with 1 required. Each association is flagged if it morphologically overlaps with the anchor concept. On the results screen, the participant sees the spread of their associations; the unconventionality of their associations; and Haiku’s interpretation, i.e. its “guess” as to what the anchor concept was from the participant’s associations.

INS-001.2: Common Ground

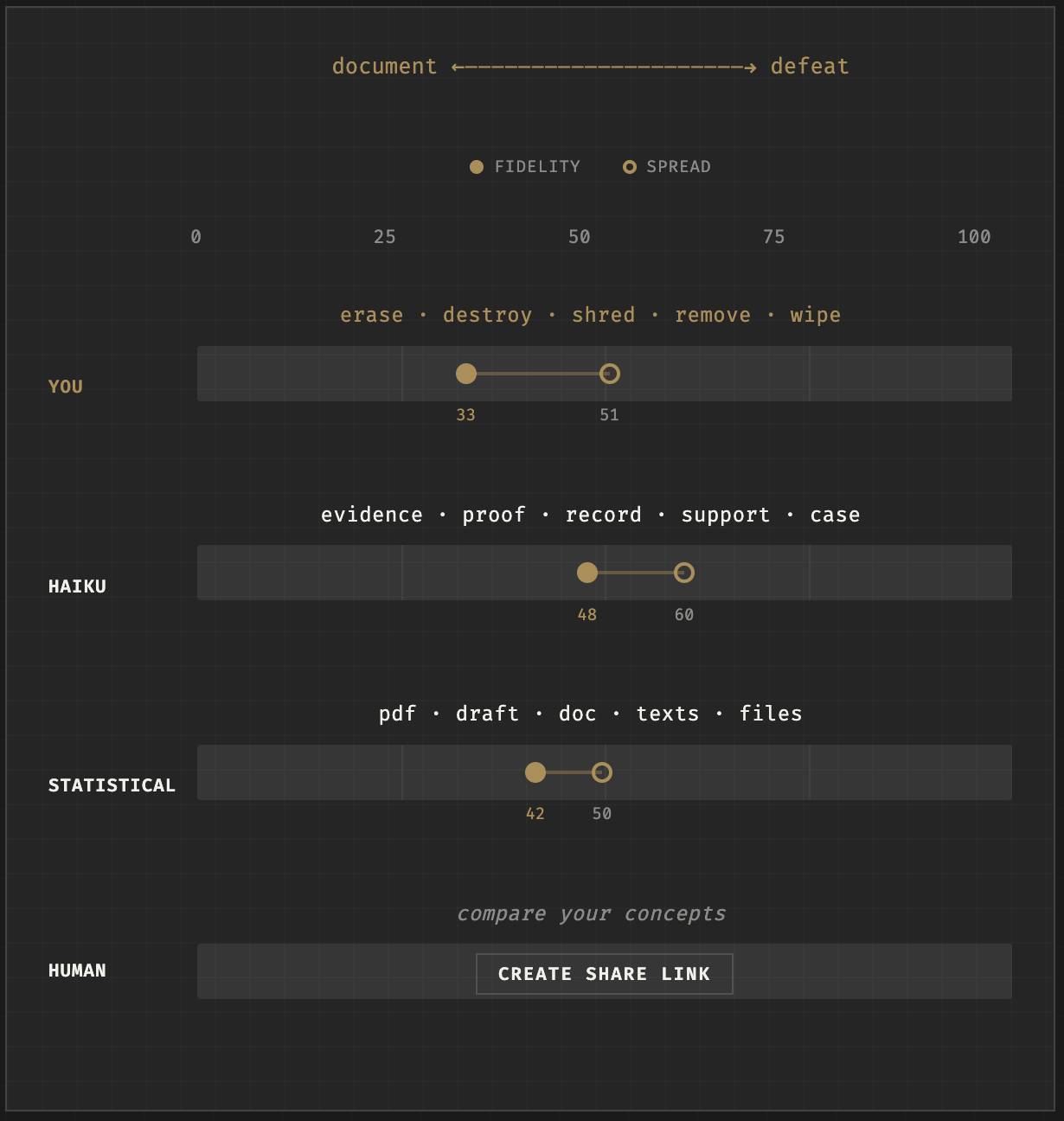

In this task, the participant generates words that are associated with two different concepts (anchor and target words). They can choose their anchor and target, or they can ask for suggestions; if they enter an input word, then the algorithm chooses 10 random words in its vocabulary pool and suggests the most distant word from that sample. In our experiments, this approach struck a balance between optimizing divergence and computational efficiency.

The participant can submit up to 5 concepts, and the user interface will provide a color warning if the submission is morphologically similar to either the anchor or target.

In the results, the participant sees their submission scored for fidelity and spread, presented in a dumbbell chart. In addition, they see Haiku’s responses and performance, as well as the performance of an embedding model (statistical). Finally, they are encouraged to share the instrument to see how their semantic associations compare to their social network.

Measures

Both instruments capture semantic association behavior through two orthogonal dimensions:

Spread measures semantic distance—how far apart your associations are in conceptual space. It is calculated as the mean pairwise cosine distance among clues, scaled 0–100.

Fidelity measures whether your associations are on task—specifically, how well your clues jointly triangulate the intended targets through complementary constraint, rather than being random, redundant, or off-topic.

Fidelity measures how well clues collectively eliminate alternative endpoints. The algorithm generates 50 nearest-neighbor foils for each endpoint, then computes:

- Coverage: Fraction of foils eliminated by at least one clue

- Efficiency: Non-redundancy of elimination (1 − intersection/union)

- Fidelity: Coverage × Efficiency

A foil is “eliminated” by a clue if that clue is more similar to the true endpoint than to the foil. Good bridging clues provide complementary constraint—different clues eliminate different wrong answers.

Full specification: MTH-002.1: Spread and Fidelity Scoring

In addition, INS-001.1 (Signal) measures the “unconventionality” and “communicability” of the participant’s associations. Unconventionality is calculated by counting how many of the participant’s associations are amongst the top 10 nearest neighbors of the anchor word in embedding space; the intent of the metric is to incentivize originality. Communicability is calculated as a binary success-failure based on whether Haiku was able to successfully reconstruct the anchor word from the associations.

Claude Haiku Calibration Baselines

As we are still collecting human data, Claude Haiku 4.5 served as the calibration reference. Its performance was as follows:

| Metric | INS-001.1 | INS-001.2 |

|---|---|---|

| Spread | 65.5 ± 4.6 | 64.4 ± 4.6 |

| Fidelity | — | 0.68 ± 0.13 |

We used Haiku’s performance to scale the spread on INS-001.1, such that the visualization spans the range 20-80 of the raw score.

Alternative Measures

While spread has empirical precedent in the literature, a measure of relevance was less straightforward. A measure of relevance would be orthogonal to spread, assessing whether a participant’s submitted concepts are on task - neither gibberish, nor random words - and how well balanced their concepts are to both the target and anchor. We explored 4 metrics: A-T distance (Relevance), Discriminative Relevance, Joint Constraint (Fidelity), and Balance. Details are in the Appendix of MTH-002.1.

| Algorithm | Core Question | Key Formula | Requires Foils? | Output Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discriminative Relevance | Do clues uniquely identify this pair? | mean of min(sim_a, sim_t) per clue, compared to foil pairs | Yes (pair foils) | 0–1 (percentile) |

| Joint Constraint | Do clues eliminate alternatives efficiently? | coverage × efficiency | Yes (endpoint foils) | 0–1 |

| Balance | Are clues distributed evenly between endpoints? | 1 − |mean(sim_a − sim_t)| | No | 0–1 |

| A-T Distance | Are clues on-topic AND varied? | Relevance: mean of min(sim_a, sim_t); Divergence: mean pairwise distance | No | 0–1 / 0–100 |

| Algorithm | Measures | Ignores |

|---|---|---|

| Discriminative Relevance | Specificity to true pair | Whether clues are diverse or redundant |

| Joint Constraint | Coverage + non-redundancy | Raw semantic quality of clues |

| Balance | Attentional allocation between endpoints | Whether clues are actually relevant |

| A-T Distance | On-topic bridging + semantic spread | Specificity (would clues fit other pairs?) |

In tests with Haiku, A-T Distance was found to be highly correlated with spread (r=-0.66). Discriminative relevance was less correlated with divergence (r=-0.113), but it was moderately correlated with A-T Distance (r=0.31), suggesting that it captures a related construct. The Balance Score failed because it was moderately correlated to spread (r=-0.239), and it also had lower variance, which would hinder its discriminative ability as a measure. The joint constraint score - which we called fidelity - had the lowest correlation to spread (r=0.055), lowest correlated to A-T distance (r=0.022), and reasonable variance (SD=0.127).

Semantic Distance

There are several approaches to calculate the distance between two words. Earlier methods used frequentist approaches: how many participants make the same associations? This was the premise behind large-scale association networks, like the Small World of Words by De Deyne et al.20 Frequentist approaches hinder us from making individual-level inferences, as we can not presume that an individual’s associations are reflective of the group. A related approach is to look for the frequency of semantic associations in large bodies of text. This method has been operationalized through the various embedding models that vectorize a word, turning a word into a high-dimensional projection of its relationship to other words.

For our purposes, we compared using Glove, the embedding algorithm used by Olson et al., against the latest embedding model from OpenAI (text-embedding-3-small-model). The two embedding models produced substantially different scores for identical word sets, with a mean difference in Haiku’s scores of 20.74 points (GloVe: 94.8, OpenAI: 74.1) and only moderate correlation (r = 0.595). With GloVe, Haiku’s scores fell far outside the human distribution, which would require either (a) concluding that Haiku dramatically outperforms humans at semantic divergence, or (b) recognizing that GloVe’s embedding geometry inflates divergence scores in ways that compromise comparability with human norms. The latter interpretation was supported by the observation that even random word sampling under GloVe yielded scores of 87.5–89.8—already above the human mean.

Communicability

Lexical approaches represent word associations from text. While our text corpora and vocabularies carry traces of our culture,23 they may not represent an individual’s semantic memory and associations, and they cannot inform whether the semantic associations between a group of individuals is shared. The sharing and communicability of semantic associations, while a source of endless fun in games like Taboo, also yields insight into shared memories, experiences, beliefs, and values. Hence, researchers are mining semantic networks to probe for latent biases in both humans33 and machines.15

The intent of designing INS-001 to be shared is to gamify the collection and social verification of semantic associations. If your semantic associations are “real,” then your friends and associates - assuming a shared set of life experiences - should be able to deconstruct your intent from your clues. This is predicated on how brainstorming sessions,34 mind mapping exercises,35 and games36 work.

V. Towards Cognitive Fitness

Competition — see how you perform against someone or something else - can create inherent rewards in some systems. Research on gamification of cognitive assessment demonstrates that competitive elements increase engagement without compromising measurement validity, and that game-based tasks can reliably measure cognitive abilities at population scale.37,19 By creating a constrained task on which AI and humans are comparable, early observations indicate that the measurement itself has game-like properties: it is measurable; the measurements are ordinal; higher levels of measurement are associated with a desirable attribute, namely creativity; and the measurements create social comparison (“I am better than…”).

These properties characterize the biomarkers that have grown in popularity through wearable devices, like heart rate variability and sleep quality measures. Just as these biomarkers are proxy measures of the influence of lifestyle, similar markers of cognition may become markers of cognitive fitness-indicators of how we are presently adapting to our information-dense environments and how we might fare in the long run.38

VI. A Double-Edged Sword

As with all endeavors of human performance, the creation of measures that drive competition invariably identify underperformers. With an AI-based measure, however, the data are already clear that systemic variables are strong predictors of performance.

The access gap. Prior digital literacy, socioeconomic status, and educational attainment predict both AI adoption and effective use. College students with higher digital literacy engage in more sophisticated ChatGPT activities, report better educational outcomes, and place greater trust in AI outputs.39 Analysis of U.S. Census data reveals that generative AI adoption follows familiar fault lines—those with higher education and income are significantly more likely to use these tools, potentially widening existing inequalities in cognitive augmentation.40

The language gap. Even among those with access, the transformer architecture underlying AI was optimized for text, biasing utilization toward the lexically advantaged: those with fluent command of syntax and grammar, who can read, write, and type with facility.41 AI systems penalize simpler grammatical structures and limited vocabulary—AI detectors, for instance, falsely flag over 61% of essays by non-native English speakers as AI-generated.42

The inheritance gap. Perhaps most troubling, even successful AI users may absorb its limitations. Participants who complete tasks assisted by biased AI recommendations reproduce the same biases when later performing the task without assistance: they inherit the AI’s errors even when the AI is no longer making suggestions.14 Critically, when participants transitioned from AI-assisted to unassisted phases, their error rates did not reduce; the AI’s biases persisted in their independent judgments.

The implications for a cognitive fitness measure are stark: those least likely to access AI-mediated assessment may need it most; those who do access it may be penalized for linguistic background rather than cognitive capacity; and those who use AI most fluently may unknowingly absorb its biases into their own semantic structure. The instrument risks becoming another marker of privilege rather than a democratizing force—unless these gaps are explicitly addressed in design and interpretation.

VII. Invitation

You are invited to take the assessments yourself.

INS-001 represents a starting point in creating comparable measures of human and AI semantic association under constraint. The intent is to apply and extend recent cognitive science that has moved beyond static measurement to examine how real-world associative thinking can be enhanced through learning: targeting the structure of semantic memory (via concept learning techniques that promote connectivity between concepts) or the associative processes operating on it (via memory retrieval strategies that encourage semantically distant connections).8

The claim underlying this work is that semantic association capacity may be sensitive to the information environment in ways that connect to outcomes of interest: creative thinking, cognitive aging, and susceptibility to bias absorption. If AI interaction is reshaping human cognition—whether by compressing semantic space, homogenizing associations, or expanding access to novel conceptual structures—then instruments designed to measure semantic divergence and fidelity may detect such changes. The direction of effect remains an open question. AI might reduce associative capacity through cognitive offloading, or it might expand it by exposing users to unfamiliar framings and alternative conceptual pathways.

The instruments still require validation, the equity concerns require careful policies to mitigate misuse, and the longitudinal questions require collaborations. Through your participation, the hope is that we can build an open dataset that allows us to investigate these questions together.

References

1. Kumar, A. A., Steyvers, M., & Balota, D. A. (2022). A critical review of network-based and distributional approaches to semantic memory structure and processes. Topics in Cognitive Science, 14(1), 54–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12548

2. Cantlon, J. F., & Piantadosi, S. T. (2024). Uniquely human intelligence arose from expanded information capacity. Nature Reviews Psychology, 3, 275–293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-024-00283-3

3. Kenett, Y. N., Anaki, D., & Faust, M. (2014). Investigating the structure of semantic networks in low and high creative persons. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 407. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00407

4. Patterson, K., Nestor, P., & Rogers, T. (2007). Where do you know what you know? The representation of semantic knowledge in the human brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 8, 976–987. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2277

5. Dehaene, S., Cohen, L., Morais, J., & Kolinsky, R. (2015). Illiterate to literate: Behavioural and cerebral changes induced by reading acquisition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), 234–244. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3924

6. Rodd, J. M., Vitello, S., Woollams, A. M., & Adank, P. (2015). Localising semantic and syntactic processing in spoken and written language comprehension: An activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Brain and Language, 141, 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2014.11.012

7. Kenett, Y. N., Levy, O., Kenett, D. Y., Stanley, H. E., Faust, M., & Havlin, S. (2018). Flexibility of thought in high creative individuals represented by percolation analysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(5), 867–872. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1717362115

8. Beaty, R. E., & Kenett, Y. N. (2023). Associative thinking at the core of creativity. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 27(7), 671–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2023.04.004

9. Tausk, V. (1919/1933). On the origin of the “influencing machine” in schizophrenia. Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 2(3–4), 519–556.

10. Higgins, A., et al. (2023). Interpretations of Innovation: The Role of Technology in Explanation Seeking Related to Psychosis. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/4464934

11. Sconce, J. (2019). The Technical Delusion: Electronics, Power, Insanity. Duke University Press.

12. Østergaard, S. D. (2023). Will Generative Artificial Intelligence Chatbots Generate Delusions in Individuals Prone to Psychosis? Schizophrenia Bulletin, 49(6), 1411–1412. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbad128

13. Hudon, A., & Stip, E. (2025). Delusional Experiences Emerging From AI Chatbot Interactions or “AI Psychosis.” JMIR Mental Health, 12, e85799. https://doi.org/10.2196/85799

14. Vicente, L., & Matute, H. (2023). Humans inherit artificial intelligence biases. Scientific Reports, 13, 15413. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42384-8

15. Abramski, K., Rossetti, G., & Stella, M. (2025). A word association network methodology for evaluating implicit biases in LLMs compared to humans. arXiv, 2510.24488. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2510.24488

16. Nielsen, T. R., Svensson, B. H., Stockmarr, A., Henriksen, T., & Hasselbalch, S. G. (2024). Automatic linguistic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: Natural language processing–based computation of a verbal fluency composite index outperforms classic verbal fluency measures in distinguishing healthy aging from dementia. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 30(8), 767–776. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617724000262

17. Gupta, R., Asgari, S., Chen, Y., Aarsland, D., Kwan, P., & Cheng, S. (2024). A genome-wide investigation into the underlying genetic architecture of personality traits and overlap with psychopathology. Nature Human Behaviour, 8, 1926–1942. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01951-3

18. Vukasović, T., & Bratko, D. (2015). Heritability of personality: A meta-analysis of behavior genetic studies. Psychological Bulletin, 141(4), 769–785. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000017

19. Pedersen, M. K., Rasmussen, M. S., Sherson, J. F., Lieberoth, A., & Mønsted, B. (2023). Measuring Cognitive Abilities in the Wild: Validating a Population-Scale Game-Based Cognitive Assessment. Cognitive Science, 47(1), e13308. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.13308

20. De Deyne, S., Navarro, D. J., Perfors, A., Brysbaert, M., & Storms, G. (2019). The “Small World of Words” English word association norms for over 12,000 cue words. Behavior Research Methods, 51(3), 987–1006. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1115-7

21. Abramski, K., Improta, F., Rossetti, G., & Stella, M. (2025). The “LLM World of Words” English free association norms generated by large language models. Scientific Data. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-05156-9

22. Cazalets, T., & Dambre, J. (2025). Word Synchronization Challenge: A Benchmark for Word Association Responses for Large Language Models. In: Kurosu, M., Hashizume, A. (eds) Human-Computer Interaction. HCII 2025. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 15770. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-93864-1_1

23. Thompson, B., Roberts, S. G., & Lupyan, G. (2020). Cultural influences on word meanings revealed through large-scale semantic alignment. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(10), 1029–1038. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0924-8

24. Robinson, W. S. (1950). Ecological correlations and the behavior of individuals. American Sociological Review, 15(3), 351–357. https://doi.org/10.2307/2087176

25. Silvia, P. J., Winterstein, B. P., Willse, J. T., Barona, C. M., Cram, J. T., Hess, K. I., Martinez, J. L., & Richard, C. A. (2008). Assessing creativity with divergent thinking tasks: Exploring the reliability and validity of new subjective scoring methods. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 2(2), 68–85. https://doi.org/10.1037/1931-3896.2.2.68

26. Olson, J. A., Nahas, J., Chmoulevitch, D., Cropper, S. J., & Webb, M. E. (2021). Naming unrelated words predicts creativity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(25), e2022340118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2022340118

27. Mednick, S. A. (1962). The associative basis of the creative process. Psychological Review, 69(3), 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0048850

28. Merseal, H. M., Beaty, R. E., Kenett, Y. N., Lloyd-Cox, J., Christensen, A. P., Bernstein, D. M., … Kaufman, J. C. (2025). Free association ability distinguishes highly creative artists from scientists: Findings from the Big-C Project. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000545

29. Ovando-Tellez, M., Benedek, M., Kenett, Y. N., Hills, T., & Christoff, K. (2024). Memory and ideation: A conceptual framework of episodic memory function in creative thinking (MemiC). Nature Reviews Psychology, 3, 509–524. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-024-00330-z

30. Risko, E. F., & Gilbert, S. J. (2016). Cognitive offloading. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(9), 676–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.07.002

31. Grinschgl, S., Meyerhoff, H. S., & Papenmeier, F. (2021). Interface and interaction design: How mobile touch devices foster cognitive offloading. Computers in Human Behavior, 120, 106756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106756

32. Gerlich, M. (2025). AI Tools in Society: Impacts on Cognitive Offloading and the Future of Critical Thinking. Societies, 15(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc15010006

33. Caliskan, A., Bryson, J. J., & Narayanan, A. (2017). Semantics derived automatically from language corpora contain human-like biases. Science, 356(6334), 183–186. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal4230

34. Brown, V. R., & Paulus, P. B. (2002). Making group brainstorming more effective: Recommendations from an associative memory perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(6), 208–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00202

35. Buzan, T., & Buzan, B. (1993). The Mind Map Book: How to Use Radiant Thinking to Maximize Your Brain’s Untapped Potential. Plume.

36. Pollmann, M. M. H., & Krahmer, E. J. (2018). How do friends and strangers play the game Taboo? A study of accuracy, efficiency, motivation, and the use of shared knowledge. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 37(5), 497–517. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X17736084

37. Lumsden, J., Edwards, E. A., Lawrence, N. S., Coyle, D., & Munafò, M. R. (2016). Gamification of Cognitive Assessment and Cognitive Training: A Systematic Review of Applications and Efficacy. JMIR Serious Games, 4(2), e11. https://doi.org/10.2196/games.5888

38. Matias, I., Haas, M., Daza, E. J., et al. (2026). Digital biomarkers for brain health: Passive and continuous assessment from wearable sensors. npj Digital Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-026-02340-y

39. Zhang, C. X., Rice, R. E., & Wang, L. H. (2024). College students’ literacy, ChatGPT activities, educational outcomes, and trust from a digital divide perspective. New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448241301741

40. Daepp, M., & Counts, S. (2024). The Emerging Generative Artificial Intelligence Divide in the United States. arXiv, 2404.11988. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.11988

41. Pava, J. N., Meinhardt, C., Zaman, H. B. U., Friedman, T., Truong, S. T., Zhang, D., Cryst, E., Marivate, V., & Koyejo, S. (2025). Mind the (Language) Gap: Mapping the Challenges of LLM Development in Low-Resource Language Contexts. Stanford HAI. https://hai.stanford.edu/policy/mind-the-language-gap-mapping-the-challenges-of-llm-development-in-low-resource-language-contexts

42. Liang, W., Yuksekgonul, M., Mao, Y., Wu, E., & Zou, J. (2023). GPT detectors are biased against non-native English writers. Patterns, 4(7), 100779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2023.100779